Chapter 4: Disruption

How plotting the Angles of Attack of the offers in your landscape reveal openings for disruptive innovation.

“Breaking an old business model is always going to require leaders to follow their instinct. There will always be persuasive reasons not to take a risk. But if you only do what worked in the past, you will wake up one day and find that you've been passed by.”

— Clayton Christensen

What will I learn in this chapter?

We’ll explain the four principle performance curves, or Angles of Attack, governing growth and innovation. You’ll learn the industrial psychology behind programming each curve and how that thinking leads to predictable behaviors among market players. You’ll discover how the four Angles of Attack each feature sinusoidal improvement dimensions (S-curves) with four stages of their own and how Missionary and Mercenary mindsets apply to them.

Here are your key takeaways:

Disruption occurs in a predictable pattern that can be represented by an S-curve. That S-curve has four stages. The most dramatic improvements to a product or service happen in Stage 2, where most of the profit potential is unleashed.

Disruption is a redefinition of what performance means to the buyer. But buyers don’t think about product strategy or the operational attributes of your business. Buyers consider offers in comparison with competing alternatives.

The Angles of Attack have counterintuitive but predictable dynamics for programming how buyers interpret the offers you might bring to market compared to competitors.

The industrial psychology known as Alpha ignores dissimilar competitors until it’s too late for them to correct their cost structure and flatten their curve of improvement from overshooting. Alphas become vulnerable to disruption from Betas, Gammas, and Deltas.

Betas can enter the market by claiming the lower-performance-demanding customers the Alpha has surrendered down-market with cheaper, simpler, more specialized offers.

Gammas redefine performance for buyers, causing Alphas and Betas to become less relevant.

Deltas imagine Gamma offers for which it might still be impossible to find a customer to buy. They might even be technologically unworkable.

Every disruption deals with a specific “job-to-be-done” (outcome the buyer is seeking) or “job-for-hire” (automating a manual task they’re already performing).

The Mercenary represents the pragmatic industrial psychology of the protector defending their territory. The Missionary represents the idealistic disruptor who seeks a better outcome for the buyer.

Doctrine and Tradecraft

If you’ve ever been brave enough to own both a cat and a dog at the same time, the following scenario might sound familiar.

A curious cat inspects everything in her way, perhaps even toppling one or two items to the floor just to see what’ll happen. The cat waltzes past the dog snoozing in his bed. The cat studies the dog, then pounces. The cat gives the dog a rapid thwack across his muzzle. The dog tries to ignore the cat and continues snoozing. But the cat thwacks him again, and before you know it, the dog snaps back, determined to preserve his cozy nap.

Disruptors are the curious, indifferent felines of the business world. Always seeking novel amusements and opportunities, they’re not afraid to go after territory they want. Thwacking away at those often bigger and stronger occupants already in the space, they eventually become impossible to ignore. Incumbents, like our canine friend, are usually content to enjoy life exactly as it is, unless a disruptor triggers them to protect their territory.

Incumbents already holding significant market share overestimate the level of control they have over their customer segments. Just like a larger dog overestimates its ability to endure the sting of a cat’s claws across its nose, they go back to sleep until the disruptor becomes impossible to ignore. They’ll continue to ignore the disruption until the pain produces a hostile response, at which point they’ll defend their territory from the invader (see Chapter 3: Control).

Acquisition of new territory drives disruptors. As long as there’s profit potential (or outside investment to fund their operations), their invasion will continue until incumbents start to defend their market segments. Incumbents, like dogs, are driven by the comfort they enjoy and the approval of a master — in the business world, this master might be a customer, an investor, or even an executive in the company. Disruptors, like cats, are driven by curiosity and indifference to the approval or disapproval of anyone but themselves.

Once disruptors discover the criterion for buyer superiority, they continue improving on this characteristic until, at last, incumbents realize they’ve been losing share. In fact, by following the incentives to move up-market into more profitable segments, where fewer buyers can afford their more premium offers, incumbents eventually discover there’s insufficient demand to support their cost structure.

When incumbents realize they’ve been disrupted, they tend to panic. They invest their capital foolishly, vainly attempting to regain their lost market share. Until their arrogance is challenged, incumbents underestimate disruptors until it’s too late to affect their impact. In Chapter 6: Humility, we discuss the need for this humbling process to close stochasms, yield results from actionable intelligence, and build cultures of confidence.

How can incumbents and disruptors innovate to stay relevant in their customer segments?

The landscape where our dogs and cats compete for territory is similar to the markets you serve and requires your constant oversight and attention. Predicting how those markets will change is a time-tested evolutionary process.

Since the 1960s, analysts, economists, engineers, and executives have described the process of innovation as an S-curve because of its sinusoidal shape. Every S-curve has four basic stages:1,2

Figure 7: The four stages of S-curve evolution

Infancy/start-up — The business grows slowly while learning foundational procedures. It establishes expectations and processes that assist scaling in Stage 2.

Rapid growth — The organization begins to take share more rapidly as customers reveal how to satisfy them and the company learns how to drive profitable growth doing so. As improvements are engineered into your offering — the operating structure that delivers your products and services (also known as “offers” as regarded by the market) — and marketers learn how to sell them, more and more buyers are attracted. This leads to a sharp upward slope in the S-curve as more diverse buyers provide higher resolution superiority criteria.

Mature Enterprise — Business growth decelerates, usually due to the entry of competitors with simpler, more specialized offers that take share down-market. This flattens the slope in the original S-curve. If an incumbent recognizes this disruption to its growth rate in time, it might invest to improve existing characteristics of its offers to steepen the slope of growth once again. But this creates a problem. Fewer buyers can afford the incumbent’s offer further up the performance curve.

Obsolescence/declining demand — Product demand flattens out and is either declining (negative slope) or holding constant (no slope) as buyer expectations decline. This often happens because down-market offers have shown enough up-market buyers that they have a simpler, cheaper alternative that’s almost as good, pulling demand downward. It also occurs because performance itself has been redefined in a new S-curve. The business must simplify its cost structure to stay competitive or develop entirely new offers to refuel its will to survive into the future.

Evaluating these stages of evolution, it is noteworthy that companies cannot move through Stage 2 (from Stage 1 to Stage 3) without gaining a thorough understanding of buyer superiority criteria. These are the intentionally selected characteristics of the offer which the market will reward with share, and which the company can use to win buyers over (see Chapter 5: Superiority). Without this understanding of superiority criteria, businesses often flame out quickly, unable to recalculate a strategy that will continue to drive growth. Superiority criteria empower businesses and their leaders to deconstruct and reconstruct their offers. This equips them to grow stronger under stress from the market by understanding changing buyer expectations, or by acting to change those buyer expectations themselves.

The mechanism of action of Stage 2 (rapid growth) is to improve performance by aligning superiority criteria to more profitable market segments where you’re seeking to take share. This will unlock the experience and knowledge needed to grow quickly.

But many entrepreneurs and business leaders misunderstand this mechanism. They are preoccupied with skipping from Stage 1 (start-up) to Stage 3 (enterprise) because they assume that Stage 2 is only about multiplying sales. In fact, increasing sales are a byproduct of understanding your buyer’s superiority criteria and recalibrating your offer’s alignment with those market segment expectations. Rapid growth is the inevitable result of this proper alignment, as well as the fine-tuning of operational advantages needed to scale future offers.

Programming superiority criteria is more often accidental than intentional. Sometimes, this results in a stroke of good luck as buyers are electrified by a new trend that stands out from the crowd. However, trendy new products are usually short-lived because the trendiest buyers are also the most fickle. Imitators spring up quickly to blunt your differentiation and win over every buyer, except the ones for whom loyalty to your brand is the greatest driver. This accidental programming also leads to leadership mistakes, including incorrectly assuming that competing offers are less relevant than they really are.

Start-up culture and venture capital revolve around explosive growth, often labeling companies as failures when growth rates flatten out. Many start-up founders have been ousted for this type of performance shortcoming. But investor expectations are especially relentless for big companies that have to answer to Wall Street every quarter. Retail and institutional investors, who’ve come to expect a dividend, buy-back, or P/E ratio in line with historical trends and forward-looking expectations, take past financial performance for granted.

Fast growth rates are intoxicating, but no offer can sustain Stage 2 forever. Eventually, growth will level off as competing offers eat into demand, leading to Stage 3 maturity. Incumbents must introduce new offers in Stage 1 to re-energize growth in new market segments. Luckily, incumbents can learn to become disruptors themselves, but only by introducing new offers into new market segments where other incumbents have grown complacent.

With this more thorough understanding of the stages of innovation, let’s explore how those stages connect to the four generic growth curves every business must choose between, based on differences in industrial psychology. This is a system we call Angles of Attack.

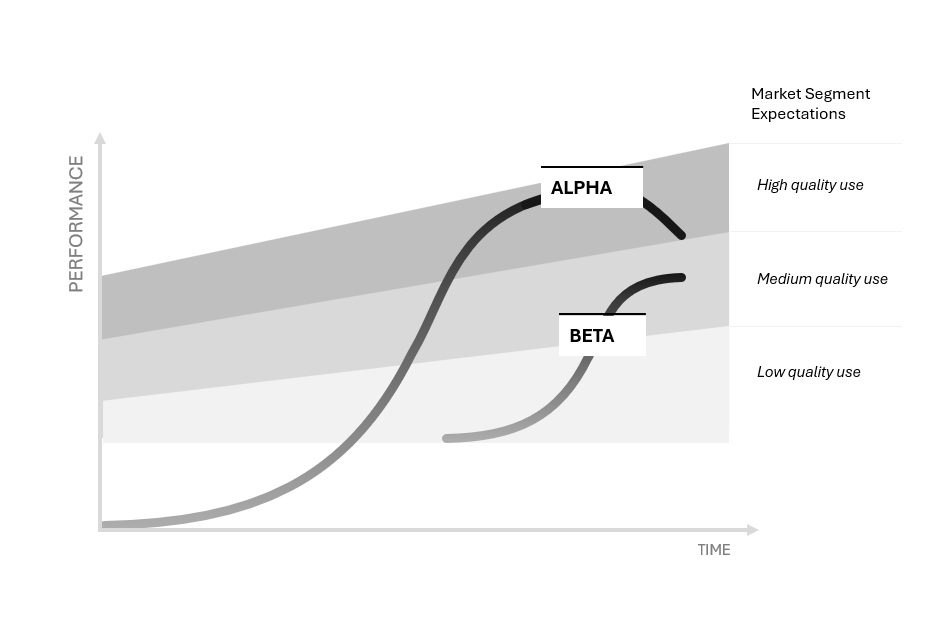

Figure 8: How Alpha and Beta evolve in relationship to one another at each stage of their S-curves

As you’ll observe in Figure 8 above, Beta enters the market in Stage 1 as Alpha is cresting into Stage 3 where profits are greatest. To prevent overshooting, Alpha is forced into Stage 4 correction down-market when Beta crests its own Stage 3 in alignment with the midsection of market expectations.

Alpha — A dominant market player that typically holds both high performance expectations and a relatively costly operating structure, commanding a relatively premium price.

Beta — Innovators who capture customers that fall below the performance expectations of the Alpha. They typically serve as more specialized, niche competitors that don’t suffer the same high-cost structure because they’ve surrendered certain parts of the value chain to specialize in the subsystems the market values most. The price buyers expect to pay is usually much lower than the Alpha, but can be far more profitable due to this cost structure advantage.

Gamma — Innovates in a new dimension of performance by bringing imaginary offer concepts into reality, confirmed by closing their first sale with a real-world customer. This process introduces Stage 1 of a new S-curve that challenges the relevance of the original market’s performance definition as characterized by Alphas and Betas. Gammas follow the four stages of S-curve evolution. Once they discover the key criterion for redefining performance, they rapidly improve their offer in Stage 2 and establish a new performance standard for buyer expectations. That new performance standard dictates who might become the next Alpha.

Delta — Offers a hypothetical solution to a problem the market doesn’t yet know it suffers from. Deltas imagine future performance definitions that even the innovative entrepreneur can’t accurately describe. But the market recognizes the unmet need a Delta will fill once a minimally viable product (MVP) is offered for sale at a price the market finds attractive. This first sale shifts the Delta up the Z-axis into Gamma.

Figure 9: Gammas redefine performance in P2, causing buyers to question incumbent offers in P1. P(n) represents future redefinitions by Deltas that might challenge predecessors when a prototype can prove the concept.

Gamma redefines performance with its new offer in P2, challenging the relevance of Alpha and Beta. However, as you’ll see in Figure 9 above, Gamma lacks superiority criteria from those buyers willing to risk buying an undiffused innovation. Only when it starts generating sales and customer feedback from early adopters for Stage 2 improvements can Gamma achieve a new Alpha S-curve in Stage 3.

Meanwhile, Delta exists only in the mind of the innovator as a hypothetical offer in a non-consuming context. Lacking market segment expectations of any kind, an infinite number of future performance redefinitions allow other Deltas to be imagined as innovations diffuse down the Z-axis. Deltas move up the Z-axis into Gamma as those hypothetical new innovations prototype themselves into existence.

Apple stands as an iconic innovator that has characterized each type of psychology at different points in the company’s history. Later in the chapter, under Applied Case Examples, we examine Apple’s iPhone in greater depth.

Like every successful company, Apple has reached a level of Alpha that must confront The Innovator’s Dilemma, as popularized by Clayton Christensen.3 Once a company has achieved Alpha and, with it, a stable status quo, it has a vested interest in maintaining that position in perpetuity, an impossible undertaking only endeavored upon by the sheer arrogance of the incumbent. As an incumbent grows complacent enjoying this status quo, the business will prefer small, safe, incremental innovations that don’t rock the boat. And they are less likely to self-disrupt with bold, risky, disruptive forays into adjacent market segments. Apple is one of the few examples that mastered this art.

How, then, can other big, successful companies disrupt themselves and find growth opportunities again as innovators?

The core of this dilemma is to figure out how much capital to allocate to new business opportunities without cannibalizing existing products, supporting services, or brands that are driving free cash flow. Shareholders will punish the company for any decline in their returns, so this balancing act must be done carefully. Most established companies are Mercenary in relentlessly seeking quick and safe returns for their shareholders. They are hesitant to invest in anything that might disrupt those expectations or is so far in the future that it can’t offer immediate returns.

A core issue is that Alphas misjudge the market by assuming perpetually elevating performance will always be valued by the best buyers. Put another way, Alphas presume that they are in charge of sustaining their superiority.

This is a mistake.

Superiority is in the mind of each buyer in the market. It is defined by the criteria that the buyer’s market segment (cluster of similar buyers) is willing to reward with share (see Chapter 5: Superiority). Misunderstanding who determines superiority implies humility is a prerequisite for both disruptor and disrupted to be teachable and responsive to changing buyer preferences over time. Arrogance — the opposite of humility — means there’s nothing anyone can teach you that you don’t already know. Until you accept your powerlessness to achieve superiority without the market’s approval, you’ll never innovate successfully.

What usually happens when the Alpha’s S-curve enters Stage 3 is that competing offers in Beta are bleeding off less attractive, down-market demand. This forces the Alpha to lower the slope of their Angle of Attack and slow the performance improvement of their offer since there’s not enough demand to support a higher cost structure. Not enough buyers can afford a more elaborate, expensive offer. And eventually, if the Alpha survives and the offer is valuable enough, only one buyer might be left at the very top of the performance curve. Alphas end up losing down-market customers with simpler needs to less expensive offers that fulfill most of their performance expectations at a fraction of the cost. Alphas will only be motivated to protect those buyers that can afford to pay for their premium goods and services at the top of the curve.

Let’s look at the example of aerospace and defense. Because of the enormous costs associated with aerospace development and weapon systems projects, the industry is underwritten primarily by the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD). The Pentagon awards nearly two-thirds of federal contracts by value and is the world’s largest buyer of aerospace and defense goods and services.4

Traditional economics dictates incumbents should drive competitors out by any means necessary. However, the worst thing a company can achieve is a monopoly. Monopolies draw the attention of regulators looking for an excuse to break them up and create the competition they’ve so carefully tried to avoid.

The number two slot in an oligopolistic market of two to four competitors is the best position for sustained profitability. If you are the undisputed leader, your dominance isn’t sustainable in the real world without massive reinvestment. And every stakeholder with an axe to grind will seek an excuse to be hostile. But this isn’t just limited to aerospace and defense.

Hostile attempts to hinder you may include appealing to a more powerful stakeholder, like the government, to force you to change what you are doing or even end life as you knew it. In September 2023, the Federal Trade Commission sued Amazon in response to multiple detailed allegations by other stakeholders. The lawsuit alleged that the company engaged in exclusionary conduct that would “stop rivals and sellers from lowering prices, degrade quality for shoppers, overcharge sellers, stifle innovation, and prevent rivals from fairly competing against Amazon.”5

This type of instability is why humility is so vital to sustained success. Leaders must be humble enough to intentionally slow their organization’s performance improvement to a more sustainable Angle of Attack. If they can’t, they risk sacrificing both long-term market share and short-term profitability.

As Alphas try to navigate this issue, they’re vulnerable to disruption from Betas, Gammas, and Deltas. Betas enter the market at a much lower performance level —which the Alpha has more or less abandoned — with offers that are much less expensive but which produce most of the value those segments of the market are willing to pay for. Those Stage 1 Betas can then push through Stage 2 to Stage 3 incredibly quickly simply by imitating the past success of the Alpha.

The primary way Alphas can protect themselves from Betas in this situation is to disrupt themselves with a new Beta offer of their own. As Apple did with the iPhone SE, Alphas produce Beta offers that can saturate the market at lower performance tiers (see Applied Case Examples).

What do Angles of Attack have to do with your customer “hiring” your offer to perform a job for them?

When an innovator enters Stage 1, they seek to address a specific “job-to-be-done.”6 Harvard Professor Theodore Levitt is famous for his marketing quote: “People don't want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!”

Clayton Christensen highlighted this principle of outcomes and the importance of properly identifying the job your customer is hiring your offer to do for them using McDonald’s milkshakes. Milkshake sales didn’t increase when the company tried to improve the product based on customer feedback about the ideal milkshake. When Christensen and his fellow researchers interviewed customers about what job the milkshakes were doing for them, they discovered that a sizable segment of buyers bought milkshakes to keep their free hand busy and stave off hunger during the boring morning commute. This research calls into question the effectiveness of traditional methods using consumer demographics, conjoint analysis, or even personas to innovate disruptive products.7

Innovators have to look at the outcome value the buyer is seeking. If you can figure out other ways to get the job done at a level of pricing, convenience, quality, and reliability that is equal to or better than current functional equivalents, you have a viable opening for disruption. Conversely, if an existing business strays too far from understanding the customer’s job-to-be-done, the company is at risk of being challenged by a competitor and losing market share.

We’ve adapted the job-to-be-done concept to job-for-hire. Jobs-for-hire help incumbent competitors recognize where technology-driven innovation opportunities are presented. We teach innovators to look for human work and then remove the human component. Innovators must see where automation or technology can deliver the outcome value the buyer wants with less human effort involved. Paying a human to work will always be costlier than using machines.

Innovators who resist replacing human effort will be at an inevitable cost disadvantage to competitors who embrace the deflationary economics of technology.

Over time, a capital investment in productive machinery will always offset the total expense of humans producing the same result. The price advantage of a technology-enabled innovator is insurmountable compared to a competitor resisting the imperative to automate.

Consider self-checkout in retail automation at McDonald’s, Target, or your local grocery store. There is a trend for decreasing human involvement inherent in all S-curves. It’s only possible to move from Stage 1 to Stage 2, or from Stage 2 to Stage 3, if you begin to remove people from the offer’s delivery mechanism in some way. There is no advantage to additional human effort until Stage 4 of the S-curve when the offer becomes nostalgic to buyers and human interaction becomes part of the value of the offer again.

It’s only when your shopping frequency or volume decline because you miss your checkout person and the relationship you’ve built that it would make sense for the retailer to reverse self-checkout back to human checkout. This rationale holds true unless, of course, shrinkage due to people failing to self-check items overwhelms the cost advantage of automation. This principle is just one of many related to predicting S-curve evolution contained in TRIZ (tеория решения изобретательских задач), the Soviet-era Theory of Inventive Problem Solving.8

But how should we identify disruptive characteristics that can be exploited for a cost advantage?

We will be discussing superiority criteria in depth in the next chapter. But first, here’s a brief overview of the specific criteria disruptive innovators use to create an unfair competitive advantage. These disruptor criteria are never reflected in the needs or wants of existing buyers. It is only through innovation and testing with newly defined market segments that criteria such as these are validated.

A simple way to remember the five dimensions of changing disruptor criteria that can alter an innovator’s perspective is abbreviated by the acronym RECON — Risk, Efficiency, Customers (and more importantly, non-customers), Outlook, and Novelty. It’ll be easiest for you to gain an appreciation for how disruptor criteria work through our applied case examples in the next section.

Applied Case Examples

When Steve Jobs had the idea for the iPhone, the project was a Delta extension of the iTunes ecosystem and the video iPod that made that ecosystem consumable for buyers. Embarrassingly, Microsoft offered the Zune in its feeble attempt to dislodge the iPod.9 They ignored almost completely the incumbent iTunes content library, which provided the insurmountably integrative advantage of the iPod’s superiority to buyers.

In many ways, Zune was the better device. The combined value of the iPod/iTunes ecosystem had been a Gamma once itself, when it boldly proposed that one could take their entire music collection (and later video) with them in their pocket everywhere. Before iTunes managed that media collection and the iPod made it portable, the principal way a listener brought their music with them was to carry cumbersome 3-ring binders of CDs. Microsoft’s proposal to buyers to replace iTunes with something new (Zune’s media content library), while upgrading a functionally satisfactory iPod, was too big an ask for almost everyone.

When Jobs introduced the iPhone at MacWorld in 2007,10 the product was a Stage 1 Gamma. The device had a mediocre camera, no 3G, a battery you couldn’t replace, and no keyboard. Yet, it was wildly significant in that it gradually completed the shift of Apple from being a computer company to being a consumer products company. The market had never seen a single product — a widescreen iPod, as Jobs described it — that could play music, make phone calls, and connect users to the World Wide Web with a desktop-like browsing experience. The concept of combining those functionalities in a single device was boldly innovative.

Many people doubted Jobs’ iPhone concept would catch on because it didn’t align with previous performance improvements focused on increments of existing characteristics. But what would happen if just enough Apple superfans bought it? It would establish a new market segment and improve the pain points in ways that shifted the definition of performance from traditional flip-style and “candybar” mobile phones and PDAs like Research in Motion’s BlackBerry.

That’s exactly what happened. As soon as Apple started delivering the first iPhones, Jobs discovered the key criteria necessary to swing Apple from Stage 1 to Stage 2 of this new Gamma S-curve. With people buying the product, the company could mine the user data Apple needed to make leapfrog improvements in the product in very short periods of time.

Competitors eventually noticed, although most were too late to interrupt the meteoric rise of this new definition of what a smartphone should be to save their own competing offers. Google quickly returned to the Android Alliance, the original inspiration for many of iPhone’s most disruptive concepts. Meanwhile, Research In Motion (RIM), Motorola, the Symbian incumbents, and even Microsoft Windows Mobile struggled to stalemate Apple’s conquest. In 2011, just four short years after the launch of the iPhone, Apple surpassed ExxonMobil to become the world’s most valuable company. Apple has continued to be among the two or three largest enterprises in human history by market capitalization, becoming the first company with a US$3 trillion value in June 2023.11,12

Apple has released many iterations of the iPhone since that first sale. Having achieved Alpha in Stage 3 with its flagship iPhone, Apple cleverly offered consumers simpler, cheaper iPhone alternatives in a Beta position down-market. The iPhone SE resulted from Apple’s recognition that the company needed to saturate the down-market with its new Beta offers. Apple became its own top competitor, and consumers could now choose between the iPhone Pro, Pro Max, or SE. This strategy would prevent outside Beta competitors — mainly Android offers from Samsung and others — from stealing away customers who were comfortable with slightly different expectations that were good enough compared to the Alpha. Buyers consider the SE, although originally marketed for its smaller size and portability, to be a “good enough” budget version of the flagship iPhone.13

What does Apple’s iPhone have to do with Star Wars, sportswear, e-commerce, AI, the Yellow Pages, wine, steel, enterprise software, pizza, and e-cigarettes?

Let’s pick up on our RECON mnemonic device from Doctrine and Tradecraft.

Risk is associated with anything that might alter the upside opportunity or downside harm associated with being a customer of your offer.

Vaping, or using e-cigarettes, is an example. Since the invention of the electronic vape in the 1960s, we’ve discovered new risks for lung damage from vaping that are even more terrifying than the risks from cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). But e-cigarettes initially seemed much safer and less offensive to non-smokers than traditional cigarettes. This perception led to widespread adoption among tobacco users. They viewed vaping as a safer alternative with fewer health risks. They also believed that vaping would ease social rejection, as people thought the secondhand smoke from vaping was less harmful to others than the secondhand smoke from cigarettes.

This shows how a perceived change in the health and social risks associated with consuming a product — or, in this case, being present when someone else is consuming it — provides an advantage to an innovator over an incumbent. Despite the mixed health risks for the user, vaping is perceived as a less-offensive way for a nicotine addict to get their fix.

Salesforce.com demonstrated how changing the risk associated with buying enterprise software would inevitably disrupt incumbents. In 1999, Salesforce proposed that software running in a centralized server architecture presented specific vulnerabilities, such as greater overhead costs, concentration of resources, and potential damage from malevolent hackers.14 The risk from cybersecurity incidents alone meant it was probably smarter to outsource software hosting to a specialist. Instead of the DIY model of safeguarding IT in-house, the specialist could more uniformly prevent and contain security breaches than any self-hosted software infrastructure.

The shift to a multi-tenant, cloud-based model — also known as SaaS or software-as-a-service — would overcome many of those issues. Because SaaS presented fewer risks than self-administration at a lower total cost of ownership, its popularity swelled and eventually came to dominate all enterprise software categories. This is especially true from a tax standpoint, when software-as-a-service is treated as a qualified and deductible business expense instead of a depreciating capital infrastructure asset.

Efficiency means an operating cost breakthrough has logarithmically reduced the total cost of production and ownership of your offer.

Walmart made it easy for people in rural communities to buy products similar to those found in suburban shopping malls and urban retail districts, all in one store and at a much lower price. Walmart’s cost structure advantage came from two chief sources: cheap real estate and investment in cutting-edge modern logistics with regionalized supply chains.

Like Walmart’s shifting economics of discount retail, heavy industrial manufacturing also has examples of efficiency disruptors. Recognizing the potential for production cost advantages, Andrew Carnegie introduced new steel manufacturing tools and techniques in his mills in the early 1870s. Carnegie reduced the cost of steel production by 79 percent over the next 27 years.15 Eventually, all integrated steel mills had to adopt his innovations to stay in business. Decades later, mini-mills did it again by using an electric arc furnace (EAF) instead of coal to melt scrap metal for production much faster than bringing a cold forge up to temperature. The time saved in foundry start-up became necessary for any steelmaker to stay in business, and the recycling aspect of scrap metal made costs radically more efficient.

When incumbents ignore the disruptive effects of efficiency innovations, they erode the competitiveness of their own cost structure simply by doing nothing. If they survive, incumbents will eventually stalemate this erosion of cost competitiveness. However, mimicking innovators usually comes too late to stem the outflow of significant market share from incumbents.

Customers represent the C in RECON. Serving existing customers will always be a high priority. Counterintuitively, you must also consider non-customers — those who have not yet bought the offer and those who stopped buying it for whatever reason.

Non-customers might simply be naïve to your offer and its benefits, or they might have discovered another solution to the problem your offer used to solve for them. Regardless of the reasons they don’t buy today, non-customers represent opportunities to acquire an infinitely larger number of buyers than you currently serve. Because a company observes a tiny minority of the potential buyer population, the most important changes to future customer superiority criteria will come from non-customers, instead of your existing buyers.

When your best customers tell you they want more of what they’re already getting, it’s not necessarily a compliment. They’re actually telling you they don’t want you to interrupt their expectations. They don’t necessarily value your offer’s attributes to the degree that they’ll pay extra for more or greater performance. Your offer simply solves a problem at a cost they find valuable. The cost of switching to a new solution might encourage existing buyer complacency with your offer as their status quo. It is easier to keep buying than to make the decision to stop buying.

There’s a saying in the restaurant business: “You can’t charge extra for a clean plate.” But what happens when there’s a pandemic?

COVID-19 showed how buyer criteria shifted radically to a sanitary dining experience as a requirement. It turns out that, sometimes, you really can charge extra for a clean plate!

Before the pandemic, people cared about cleanliness. But once a novel and poorly understood virus called into question how to avoid exposure, buyers placed a higher premium on sterile products uncontaminated by human contact.

Although many businesses suffered during lockdowns, Domino’s Pizza exploited the technology innovations it had already been investing in. Domino’s emphasized the benefits of its existing mobile-app ordering in connection with its new automated point-of-sale pickup system to ensure customers could get their pizza without interacting face-to-face with customer service personnel. Customers were willing to switch allegiance for contactless pickup. Because Domino’s could meet the increased demand for these criteria, the business profited as others suffered. Domino’s brought on 10,000 new workers, and U.S. same-store sales went up by 16.1 percent from Q2 of 2019 to Q2 of 2020.16,17,18,19,20

Non-customers are the people who are not buying but who are sending signals to you about what you need to do differently to bring them into the market as buyers.

Non-customers are critical to understanding disruption because they reveal innovation opportunities you’ve probably never considered. When Alphas overshoot most of a market segment’s performance expectations, a Beta innovator could turn non-buyers into buyers by simply reducing the complexity or cost of consumption. Non-customers help you ask what’s missing from your offer to get them to buy. Better yet, none of your competitors are asking those questions, either!

When Betas identify and close the cost-complexity gap, they take share by attracting overshot customers at a lower price level, which is free of the inferior complexity Alphas offer. Sometimes, that complexity is in the form of other buyers’ sophistication levels.

Yellow Tail, an Australian wine company, used this concept by appealing not to existing wine drinkers, but to beer drinkers who were “wine curious” yet felt wine drinking was too pretentious for them. Beer drinkers might have also felt like drinking wine was too expensive or too complicated for them to change their drinking habits. The perception of sophistication wine drinking sends to non-customers is intimidating enough to keep non-customers from even trying it. Yellow Tail challenged the perception of pretentiousness with Super Bowl ads that made wine-drinking sexy, fun, and just as simple as cracking a beer.

Outlook asks which market segments are fastest growing and, as a result, most attractive based on compound annual growth rate (CAGR) compared to the other market segments you might sell into.

If you accidentally innovate an offer in a market that isn’t growing or might even be shrinking, your offer will require a level of capital investment unrecoverable in the future. This is especially true when incumbents are already defending their share of buyers from one another. It’s critical to evaluate the growth potential of market segments before allocating capital to establish a market share position.

Imagine you’re an incumbent Alpha in a slow-growing or even shrinking market segment. You notice a growth opportunity right next door in an adjacent market. With a very small tweak or change to your offer, you could unlock that adjacent job-for-hire and capture new, faster-growing market share without substantial capital investment. The easiest growth an incumbent might ever encounter is by innovating in adjacent, faster-growing market segments naïve to the incumbent’s original offer.

Compare looking for a service provider in the yellow pages of your phone book with a site like Anji (formerly Angie’s List). Anji started in 1995 when founder Angie Hicks and her business partner, William Oesterle, implemented a rating system of service providers for homeowners based on data collected door-to-door. If Hicks had been competing with the yellow pages, she might have sold her ratings in a printed format. But as the Internet gained traction with consumers as a source of information like hers, it was more advantageous for Hicks to build a Web-based index of service providers who paid for premium placement in her directory.

As an example of the combined effects of risk, efficiency, and now non-customer segmentation, the website enabled Hicks to disrupt other advertising services by connecting the sales leads her site generated for service providers to the work that was ordered. This made the marketing investment for advertisers much more measurable.21

Novelty refers to whether or not your offer is fundamentally new and unexpected by buyers or incumbent competitors in the market. Novelty typically centers on technological innovation, which your market doesn’t yet know it needs.

One timely example includes the evolution of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Much like the reaction of scribes to the advent of the printing press, which kicked off the Industrial Revolution centuries ago, many knowledge workers fear the impact of AI on their employability.

Many are right to worry.

Anywhere patterns of work can be reduced to a language model, it’s inevitable that a machine will perform as much of that value chain as possible. Those providers of that value chain who resist will be unable to sustain their business model economically. The price of their offer will be so many times higher than the offer benefitting from AI that no buyer will be willing to reward them with share — or, in this case, a career.

In early 2023, OpenAI unveiled ChatGPT. Google, Microsoft, Meta, and many others followed with their own Generative AI platform announcements. Successive generations of the Large Language Model (LLM) system have proven useful in batching work processes that otherwise require a human to execute them. Content creation, legal services, health care, banking and finance, and even education and teaching are being automated by machines trained in the languages humans use to communicate with one another to perform most or all of the tasks associated with each job.

The most poignant example is software engineering itself. Computer Science departments at top universities around the world are recognizing that the cost-per-line of code generated by a human alone can be many times greater than if a programmer uses ChatGPT to draft their app quickly. Someday soon, it will no longer make economic sense to hire programmers who do not use GenAI to take a first cut at whatever they’re developing.

Eventually, we recognize threats like GenAI in the workforce when we see legal and political action to halt or slow its progress. The Hollywood writer’s strike of 2023 set the release schedule of America’s top cultural and IP export back by more than a year. But the strike put in place safeguards to protect writers and actors from having their work used to train LLMs to reproduce similar products. GenAI is so disruptive of a novelty that laws are being written to buy time for humanity to figure out its purpose again in a knowledge economy where humans are no longer the most knowledgeable.

To defend itself against Amazon, Walmart knew it had to contend with Amazon Prime.22 Walmart leaned on its vast store network advantage to build out its consumer e-commerce business.23 Amazon is countering Walmart’s territorial footprint by developing physical locations of its own. When Amazon acquired Whole Foods, the move didn’t take much share from the grocery side of Walmart’s sales. But it gave Amazon a network of upscale, branded storefronts for customer service fulfillment. Both companies have expanded into services such as pharmacy and even streaming video.24 Amazon and Walmart stand out from other corporate titans because they understand how to disrupt themselves better than most of their peers. Both companies accept thinner profit margins to scale their business for maximum market penetration.

Mercenaries are all about winning zero-sum games, but that is seldom how disruption unfolds. Mercenaries play to win; Missionaries play to keep playing.

The Missionary asks how to create new value for unserved customers. They are willing to set aside short-term financial incentives to focus on long-term, innovative change that brings value to the world at large. Missionaries understand profit is a byproduct of innovation, not its primary purpose.

Patagonia, well known for its corporate values around climate change, is a good example of a Missionary mindset. In the early 1970s, the climbing equipment innovator replaced its dominant position in the market for steel pitons with aluminum chocks. Steel pitons were hammered between cracks in rocks to anchor climbing ropes and damaged rock faces over time, as larger and larger pitons were required to fill the gap. Aluminum chocks did not cause the same kind of damage. Within one year, Patagonia completely transformed its business from steel pitons to aluminum chocks, and the market followed Patagonia’s lead.

In another example, Patagonia fought to protect a local surf break from development. The company later donated millions to groups seeking to save or restore natural habitat. When Patagonia moved beyond equipment and into clothing, it became the first company to teach the concept of layering to outdoor enthusiasts. Just as they had discontinued steel pitons, Patagonia disrupted itself and discontinued its own fabrics when they had a design for superior materials.

Patagonia invested in providing mainly organic foods at its cafeteria. It also put money toward on-site childcare for employees. In September 2022, founder Yvon Chouinard transferred ownership of the entire business into the Patagonia Purpose Trust and Holfast Collective. Every dollar not reinvested in the business will be donated to protect the planet.25

Filmmaker George Lucas is another example of the disruptive Missionary mindset. In 1977, when producing the first Star Wars film, Episode IV — A New Hope, Lucas encountered a myriad of hurdles. These included lackluster production support from 20th Century Fox, struggles with special effects technology, and difficulty getting actors to sign onto an unknown project.

But Lucas had a longer-term vision for what the project could become. He had faith that the Star Wars universe could achieve long-term global success. So, he gave up $500,000 of his paycheck in exchange for ownership of Star Wars’ perpetual merchandising and sequel rights.

This willingness to make short-term sacrifices for long-term gains represents how Missionaries see their Stage 1 projects into Stage 2. It’s difficult to calculate the exact value of how much cumulative wealth Lucas has earned from this tiny, early sacrifice. But, there’s little doubt that — with the project evolving into more than a dozen movies, TV shows, entertainment merchandise, theme park attractions, and eventual acquisition by Disney — Lucas’ decision proved to be one of the savviest anyone in Hollywood has ever made.26,27

Which mindset is strongest in you?

“Undermine their pompous authority, reject their moral standards, make anarchy and disorder your trademarks. Cause as much chaos and disruption as possible, but don’t let them take you alive.” — Sid Vicious

Disruption is the first of our characteristics to truly narrow the advantage between Missionary and Mercenary in a noticeable way. While Stage 1 of the new S-curve requires a Missionary mindset to accept the meager profit incentives motivating the innovator, the Mercenary quickly takes over when the new offer proves to have traction with a defensible target market segment in Stage 2.

Because you seldom turn a profit in Stage 1, Mercenaries aren’t interested in disruptive new Gammas. However, when buyers begin to demonstrate how the faster growing new offer can achieve Alpha during Stage 2, the Mercenary wakes up and seizes control. By the time you reach Stage 3, the Mercenary is fully in charge, and saturation down-market with competing Betas is the path to future market dominance, as Apple did with the iPhone. A Mercenary would never disrupt smartphones with a widescreen iPod; they’d simply make a better BlackBerry. While the advantage of the Missionary quickly turns Mercenary to exploit the profit motive, the Mercenary seldom starts with a disruptive offer in the first place.

The Mercenary exemplifies the industrial psychology of the Alpha, which is to defend its existing market share from incursion by other Alphas. Like a sleeping dog will discount the threat from any animal perceived to be weaker than them, Alphas will discount the threat from any competing offer that lacks advantages similar to those the Alpha provides.

Direct confrontation by a recognizable threat will trigger the incumbent Alpha to prepare its defense or preemptively counter-attack. At a minimum, the incumbent will attempt to warn the invader from threatening what belongs to them. To defang the incumbent and avoid triggering their defensive instincts — ensuring the incumbent is more bark than bite — disruptors must convince the incumbent they are not a threat.

If your work supports a Gamma disruptor, you will need teammates and stakeholders alike to accept the Missionary’s meager profit incentives required to sustain Stage 1. However, once they see the potential for market dominance emerge in Stage 2, your job will become easier as you support their Mercenary instincts.

As your Stage 3 Gamma takes market share away from the Alphas and Betas who previously owned it, your Missionary must continue to look out for new disruptors of your own. Disruptors have a limited future without complacency on the part of those who occupy the market segments they wish to capture.

As you achieve Alpha, beware of falling into the same trap as those incumbents who went before you.

Memoirs

Back in 1995, when Aurora WDC was just getting up and running, Arik was still exploring what the business might do in the world. One of his first gigs was an analysis for a very large emu ranch in California — 50,000 breeding pairs! They needed a five-year global compound annual growth rate (CAGR) forecast for their meat, feathers, oil, and other emu products.

Despite the fact Arik didn’t know how to do the work when he pitched it, he won the project anyway. He proceeded to learn everything he could about emus, CAGR methodology, and how to deliver a client project successfully. The client was happy with the output Arik taught himself how to generate and, like every Missionary with a Stage 1 Gamma, his fee was far below market value. The engagement gave him a first project to discover an offer the market would pay for while building his confidence to learn whatever was needed to succeed.

Today, Aurora’s team of analysts have much deeper experience and more specialized skills for generating insights than Arik did back in the day. In fact, we seldom take on projects we haven’t done before (unless you’re Arik). That early lesson became one of Aurora’s principles for innovation. Continuing today, Arik seldom pursues work he’s had an opportunity to practice before. But the business can’t succeed constantly shifting gears into new territory.

In 1998, Arik was killing time in his car in a parking garage in Madison, Wisconsin. While waiting for a lunch meeting to begin, he started writing an essay about what the MCI-WorldCom merger was signaling to the telecommunications market. He published his analysis online in an early version of what we later came to call blogs, which Arik eventually pushed out about events in the business world every day for several years. As he switched gears to focus on his lunch meeting, Arik forgot all about the essay he had published.

That autumn, Arik was invited to give a competitive intelligence workshop in San Diego at a large conference called CI4IT. The conference regularly drew 400 to 500 professionals from the top companies in Silicon Valley and beyond. At one of the opening keynotes, the head of intelligence for GTE, one of the Baby Bells, asserted that the most insightful thing he had read that year about the competitive dynamics in the telecommunications industry was Arik’s short little essay. He not only recognized Arik’s name on the conference agenda, but also asked out loud if Arik was in the audience and invited the attendees to give him a standing ovation for his insights.

That experience was pivotal in multiple ways. First, it ignited Arik’s enthusiasm for Aurora to make a name in the competitive intelligence (CI) industry. He realized how many large companies needed guidance like his and saw the opportunity for Aurora to disrupt incumbents. He also saw genuine interest in the insights he had to offer — even short, analytic essays on topics where his knowledge was fairly thin. Arik’s lack of telecommunications industry experience and expertise was an ironic advantage to generating insightful analysis because he didn’t know what subjects were off-limits. He simply wrote what he saw happening and what the market might have missed.

Our first Beta business, Aurora Global Professional Services (GPS), disrupted incumbent CI firms by rethinking our approach to staffing. Alphas bragged about having so many analysis and insights personnel in their expensive, big city offices and even quoted headcount figures in their marketing. Lots of headcount might impress Fortune 500 clients, but it’s no guarantee you’ve got the best analysts on your team.

We decided to focus on the outcome clients sought, rather than window-dressing. We pioneered the development of a business model built around contracted, independent human intelligence (HUMINT) elicitation and collection specialists around the world. Aurora doesn’t need to control an independent analyst’s schedule, force them to use our equipment, or follow our directions in the interviews they conduct with subject matter experts (SMEs). They might not even be conducting their interviews in a language we understand. We simply need their skills and experience talking with knowledgeable sources, while maintaining Aurora’s ethical standards above and beyond the accepted boundaries of our clients and the industry at large.28

Saying no to the status quo

In 2018, I had a phone conversation with our director of competitive simulations, Tim Smith. Most war games we designed and facilitated for clients used satisfiers and drivers as criteria for hypothetically scoring market fit and the outcome of competitive confrontations. But I saw the potential to add a third criterion — disruptors. Knowing we had a big war game facilitator school coming up for a key Alpha client, I proposed this idea to Tim.

Tim was skeptical. A veteran of war games of a different kind in the U.S. Army, Tim knew it was hard enough to get people engaged with satisfiers and drivers. Why in the world would we add yet another element for clients to worry about?

The Mercenary in me understood where Tim was coming from. Maybe it was better to let sleeping dogs lie rather than introduce another abstract variable. However, my Missionary side was convinced that adding disruptor criteria would elevate the accuracy of war game scenarios and equip us to design more actionable insights and outcomes. It would help us confront the Alpha complacency so immune to change from within, encourage new thinking about how to compete as a startup might, and enable us to discover how to help our clients bring disruptive new product concepts to market.

We discussed how to position the idea with an Alpha client, a nationwide retail leader. I maintained that adding disruptors would improve the way they did wargaming. Tim agreed to propose the concept to the client, but I agreed in return to let it go if they hated the idea.

About a month later, Tim called me back. He told me he’d introduced the concept to the retailer’s C-suite leadership and that they’d loved it. We built disruptors into their facilitator training — and into every war game we’ve designed since.

It would have been easy for us to continue with the status quo and leave out this improvement to the way we design war games. But because Tim was willing to take a risk and pitch something new to one of our most valued clients, we delivered a richer workshop experience and more actionable results that changed the way our clients have thought about wargaming ever since.

— Arik

Aurora’s second Beta brand, FirstLight, provides intelligence and insights software to the same kinds of corporate clients who rely on Aurora GPS. It synthesizes data from thousands of Internet sources, as well as proprietary systems and internal subject matter experts.

The inception of the business in late 2005 hinged on adapting Drupal, an open-source content management system (CMS), rather than writing our own intelligence software from scratch. At the time, Drupal was the most sophisticated CMS and had the largest developer community. This strategy offered an adaptable starting point and support from contract developers, should we encounter problems scaling up. We deliberately decided on an open-source architecture to avoid writing and maintaining the whole code base ourselves. We could also avoid legal challenges if we inadvertently infringed on somebody else’s proprietary or protected feature set.

This approach enabled rapid prototyping of our new software-as-a-service platform, attracted bootstrap funding from our first few sales, and started improving the platform based on customer feedback. We could move from Stage 1 through Stage 2 of this new S-curve despite not having an army of developers on staff or external venture capital with which to hire them. We are now maintaining our FirstLight Alpha for enterprises. But we’re also introducing less expensive software editions for teams and individuals that can take share from competitors at lower tiers of the market.29

Aurora also sees disruption opportunities in how professionals within the CI industry network, connect, and upskill to solve common problems. Through our third brand, RECONVERGE, we have hosted annual symposia, small groups, and webinars, which are designed to let people share insights, collaborate, and learn. Other projects keep this spirit of learning alive, such as DEMOlition, which turned into a short documentary film called Angles of Attack. For this 2018 project, we worked with three startup companies to reveal the frailties in their offer, operating model, and superiority criteria for their target market segment buyers. The objective was not just to remove the frailty, but to transform that frailty into a strength.

One of the subject companies, T-Care, demonstrated a Gamma, redefining performance for their market. Their existing strategy of selling annual software licenses to social service agencies was unsustainable due to the lag time of receivables from this type of customer. DEMOlition revealed that they could give the software away and sell the anonymized data their system generated. This fundamental change of business model would allow them to finance their operation and maintain the software while dramatically enhancing the value of their offer. This shift transformed existing buyers into no-charge beneficiaries, and it discovered a new buyer of the data insights that could become the systemwide benefactor.30

Throughout the development of our business and brands, we’ve innovated a little at a time. We’ve had to tackle many short-term hurdles that required us to be ruthlessly Mercenary, and we’ve also worked hard under a Missionary mindset to consider how our brands complement each other and contribute to our long-term vision for Aurora. You can find a similar blend of Missionary and Mercenary mindsets within your unique circumstances.

We hope our story about how the corporation and its businesses have evolved will inspire you to begin your own disruption journey.

Questions to Activate Control

Disruption can be defined as changing the rules. Although many innovators focus on massive changes that reinvent the game completely overnight, innovations that occur incrementally over time can be just as disruptively valuable.

Competitiveness requires that you understand which Angle of Attack — Alpha, Beta, Gamma, or Delta — suits the criteria of the market segment you seek to disrupt. This understanding is also important because each Angle of Attack is predictable in the mistakes it tends to make. Awareness of those typical mistakes should give you the confidence to avoid them. It also allows you to handle new entrants, depending on whether they are friend or foe.

Here are a few questions for you and your teammates to provoke discussion about how you handle disruption, whether you’re the incumbent being disrupted or the disruptor redefining performance for a new offer that changes the rules:

How do the applied case examples we shared reflect the circumstances your business is dealing with today or has dealt with in the past?

What stage of the S-curve are each of your company’s offers experiencing today? How will you move to the next stage or adjust your Angle of Attack to maintain your position in a more desirable place on the curve?

Where is the disconnect between your customer’s job-for-hire and your offer’s definition of performance?

References:

Donna Weidinger, “Guide to S-Curves: Definition, Stages and Inflection Points,” Indeed, July 28, 2022, https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/s-curve.

Ken Fordyce, “Some Basics on the Value of S Curves and Market Adoption of a New Product,” April 1, 2020, https://blog.arkieva.com/basics-on-s-curves/.

Clayton Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma, (Boston Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2016).

“Home of the Nation’s Defense Infrastructure,” Arlington Economic Development, accessed January 17, 2023, https://www.arlingtoneconomicdevelopment.com/Key-Industries/Aerospace-Defense.

“FTC Sues Amazon for Illegally Maintaining Monopoly Power,” Federal Trade Commission, accessed October 3, 2023, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/09/ftc-sues-amazon-illegally-maintaining-monopoly-power.

“Clayton Christensen: The Theory of Jobs to Be Done,” Harvard Business School, accessed December 26, 2023, https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/clay-christensen-the-theory-of-jobs-to-be-done.

Carmen Nobel, “Clay Christensen’s Milkshake Marketing, Harvard Business School, February 14, 2011, https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/clay-christensens-milkshake-marketing.

“What Is TRIZ,” The TRIZ Journal, accessed January 17, 2023, https://the-trizjournal.com/what-is-triz/.

Jack Denton, “10 years after its demise, a requiem for the Microsoft Zune, the little gadget that couldn’t,” Fast Company, June 15, 2022, https://www.fastcompany.com/90761088/a-requiem-for-the-microsoft-zune-the-little-gadget-that-couldnt.

Superapple4ever, “Steve Jobs Introducing the iPhone at MacWorld 2007,” YouTube, December 2, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7qPAY9JqE4.

Ryan Vastelica and Bloomberg, “Apple just made history by becoming the first company with a $3 trillion market value—‘and its lock on the consumer is only getting stronger,’” Fortune, June 30, 2023, https://fortune.com/2023/06/30/apple-history-3-trillion-market-value/.

Luke Dormehl, “Today in Apple history: Apple becomes world’s most valuable company,’” Cult of Mac, August 9, 2023, https://www.cultofmac.com/496476/apple-history-most-valuable-company/.

Carrie Marshall, “The history of the iPhone SE,” TechRadar, March 14, 2022, https://www.techradar.com/news/the-history-of-the-iphone-se.

Alexia Duvigneau, “The 10 Benefits of SaaS Vs On-Premise,” Beekeeper, August 29, 2022, https://www.beekeeper.io/blog/onpremise-vs-cloud-benefits-saas/.

Sean Adams, “Steel: Carnegie and Creative Destruction,” University of Florida, accessed January 18, 2023, https://ufl.pb.unizin.org/imos/chapter/steel/.

Greg Ip and Agnus Loten, “Most Businesses Were Unprepared for COVID-19. Dominos Delivered,” Wall Street Journal, September 4, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/most-businesses-were-unprepared-for-covid-19-dominos-delivered-11599234424.

Laura Reiley, “Pizza delivery in a pandemic: Domino’s is hiring 10,000 workers,” The Washington Post, March 19, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/03/19/pizza-delivery-pandemic-dominos-is-hiring-10000-workers-during-outbreak/.

Domino’s Pizza, “Safe Food Delivery,” accessed December 26, 2023, https://media.dominos.com/safe_food_delivery/.

Stuart Lauchlan, “Pandemic pizza — Covid-19 takeaways from Domino’s as digital transformation work pays off,” Diginomica, April 27, 2020, https://diginomica.com/pandemic-pizza-covid-19-takeaways-dominos-digital-transformation-work-pays.

Amelia Lucas, “Domino’s Pizza U.S. same-store sales soar 16% as more customers order delivery,” CNBC, July 16, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/16/dominos-pizza-dpz-q2-2020-earnings-beat.html.

Dmitry Lipinskiy, “The Rise and Fall of Angie’s List,” Roofinginsights.com, October 31, 2019, https://roofinginsights.com/blog-the-rise-and-fall-of-angies-list/.

Leo Sun, “3 Ways Wal-Mart Stores Is Countering Amazon.com,” The Motley Fool, July 7, 2016, https://www.fool.com/investing/2016/07/07/3-ways-wal-mart-stores-is-countering-amazoncom.aspx?awc=12195_1673917597_ba3b9d90487947d39b7f98d5eda02f7e&utm_campaign=101248&utm_source=aw.

Melissa Repko, “Walmart is using its thousands of stores to battle Amazon for e-commerce market share,” June 2, 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/06/02/walmart-bets-its-stores-will-give-it-an-edge-in-amazon-e-commerce-duel.html.

Blake Morgan, “7 Ways Amazon and Walmart Compete — A Look at the Numbers,” August 21, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/blakemorgan/2019/08/21/amazon-versus-walmart-goliath-versus-goliath/?sh=87c54524674f.

“Company History,” Patagonia, accessed January 17, 2023, https://www.patagonia.com/company-history/.

James Rainey, “Disney’s ‘Star Wars’ Merchandise Gives the Force to Younger Generation,” Variety, December 2, 2015, https://variety.com/2015/biz/news/star-wars-the-force-awakens-merchandise-disney-1201651244/.

Devon Forward, “Why George Lucas Took a Half-Million Dollar Pay Cut on the First Star Wars Movie,” Looper, December 3, 2020, https://www.looper.com/288092/why-george-lucas-took-a-half-million-dollar-pay-cut-on-the-first-star-wars-movie/.

“Aurora GPS,” Aurora Worldwide Development Corporation, accessed January 18, 2023, https://aurora-gps.com.

“FirstLight,” Aurora Worldwide Development Corporation,” accessed January 18, 2023, https://getfirstlight.com.

“RECONVERGE,” Aurora Worldwide Development Corporation,” accessed January 18, 2023, https://reconverge.net.