Chapter 5: Superiority

How alignment of your superiority criteria with market performance expectations is the most important choice you have dominion over to make winning programmable.

“Talent hits a target no one else can hit. Genius hits a target no one else can see.”

— Arthur Schopenhauer

What will I learn in this chapter?

Superiority analysis serves as an open-source system to support the Angles of Attack we learned in the last chapter. You’ll discover why it’s important to concentrate your power on dominion control factors and program your superiority criteria to align with market performance expectations.

You’ll also learn the three main categories of superiority criteria — satisfiers, drivers, and disruptors — and how they define the characteristics your customer market segment will prefer. Finally, we’ll foreshadow an Investment-Grade Conjecture (IGC) that can be tested against helpful or hostile landscape stakeholders during Simulation.

Here are your key takeaways:

Superiority is a deliberate choice, not a random roll of the dice. Achieving superiority requires changing your mindset and focusing your attention on dominion control factors over which you have exclusive governance.

Superiority analysis is the process of evaluating and prioritizing superiority criteria — the satisfiers, drivers, and disruptors each market segment expects in the offer they’ll select. In this way, superiority can be considered the commercial application of Control Factor Theory. This will allow you to develop an investment-grade conjecture — the educated guess your financiers will most enthusiastically support.1,2,3,4

You’ll see superiority applied to cases as diverse as incandescent light bulbs, photo acetate film, wristwatches, automobiles, the fitness industry, and even Starbucks.

Doctrine and Tradecraft

Imagine you’re a Scottish fellow in the mid-1800s. You’ve just immigrated with your wife and children to Yorkshire, England, to work as a miner. Your family would like a companion animal that would befriend the family but, as a working pet, not be too much of a burden on the household budget.

Those criteria might include the cat we met in the last chapter. But the dog would be a much better fit. Those criteria also eliminate many other choices — goats, hamsters, bunny rabbits, birds, hermit crabs, and even fish.

Basic table stakes — satisfiers — define the bare minimum required for acceptance and exclude almost all of the alternatives. Bunnies and hamsters are cuddly, but they can’t earn their keep. Fish, birds, and livestock aren’t generally considered very friendly; you might even eat them.

But what if there were more precise criteria — drivers — that zeroed in on a superior choice?

Your spouse insists that your new four-legged family member, whether cat or dog, must settle down at night, alert her to strangers, go on nice walks with the children during the day, and not destroy your humble abode by getting into the food supply or relieving itself indoors. Understanding those drivers, you know for sure you want a dog instead of a cat. But to keep its food consumption under control on the meager wages of a Yorkshire miner, that dog will have to be a smaller breed.

Because you’re living in 1800s England, vermin are a problem for everyone, not only in the mine where you work, but also in sewers, kitchens, and stables. Rats keep getting into your pantry and occasionally even lead to outbreaks of plague. You need a dog breed with two cat-like characteristics: It’s got to be small; and it’s got to exterminate the vermin.

The perfect breed that meets all of your criteria doesn’t exist, but the owner of a nearby textile mill wants to breed dogs to control the rats in his building, since cats can’t keep up with the job. The mill owner has assigned the breeding of the dogs to your neighbor’s wife, and she’s just whelped a new litter. The mill owner doesn’t want the runt of the litter to stay in the breeding pool, but the scrawny little pup will work just fine for your family. So, as soon as it’s ready to leave its mother, you bring it home.

Since all your neighbors have rat problems like you do, they’ll love a puppy that earns its keep, too. They might even pay extra for one. Although this would reduce demand for larger breeds like Great Danes or English Mastiffs, tiny, rat-hunting terriers would perform all the necessary jobs-for-hire you and your community have for dogs: protect your food supply and health; be good, friendly, economical watchdogs; and occupy the kids without damaging your property.

Scottish weavers immigrating to Yorkshire did precisely as this story describes, developing what’s now known as the Yorkshire Terrier.5 The criterion of eliminating disease-causing rats is a disruptor and was only possible by breeding an entirely new canine. The idea that a dog — not a cat — would exterminate rodents was unthinkable before the Yorkshire Terrier was bred to fulfill that very role.

The case above demonstrates how an innovator might use different superiority criteria. It helps to focus your work on factors the market is willing to reward you for. These criteria set foundational boundaries, differentiate themselves from competitors, and achieve Alpha by introducing a performance dimension that used to be unavailable.

The case above also shows how the three types of superiority criteria relate to innovation and S-curves. Companies that deliver minimum satisfiers take share only at lower performance tiers in Beta. Still, they won’t be competitive in higher performance segments of the market until they introduce criteria that customers pay extra to enjoy, prefer over functional equivalents, or meet new needs.

Let’s take a closer look at each of the three superiority criteria and their differences:

Satisfiers — Characteristics that are necessary table stakes of the offer but that won’t initiate a switch by buyers or threaten the share of incumbent suppliers. The offer must include these elements but is only rewarded up to a threshold of expected performance.

Under-delivery of satisfiers means the risk of buyer flight is almost guaranteed and is your most important cost of doing business. If performance exceeds the expected threshold, the customer will not pay extra or switch from an incumbent source. Switching costs are one of the greatest expenses customers will ever be willing to bear, and switching must only be done for very important reasons.

Producing beyond the threshold is wasteful and adds unnecessary operating expenses to the company’s cost structure. Everyone wants to exceed their customers’ expectations, but if you don’t trim back excess performance — value that is not valued — Beta companies will see an opening. Betas will use your over-delivery against you as a cost-structure disadvantage that you might not be able to recover from. You control only your willingness to overdeliver or your commitment to trimming back.

Drivers — Characteristics that make such a difference to the customer that they will choose your offer over all other options. This includes the option not to buy anything at all.

Drivers enable you to take share from other providers in the market, but they are not unassailable. Drivers that successfully take share force competitors to imitate those improvements on your offer simply to stop losing customers. They might even decide to leapfrog your offer by improving your driver to outperform your original innovation.

Drivers are temporary, and it’s best to see them as providing only a temporary competitive advantage.6 The ideal scenario is that your driver is so superior in the buyer’s mind and unique to you alone that it induces surrender from competitors. This surrender will, de facto, mean your driver criterion is the new “industry standard.” This scenario is difficult to achieve because competitors won’t let you redefine the new industry standard without a fight. Likewise, regulators such as the U.S. Federal Trade Commission are charged with breaking up monopolies and cartels, which destroy free market competition and can lead to price gouging of buyers. Beware: If all your competitors surrender to your industry standard, as planned, you will be at risk for regulatory interference in your IGC.

Drivers have only these three possible responses from competitors: imitate to stalemate, leapfrog to outperform, or induce surrender as the new industry standard.

Disruptors — Characteristics the market finds surprising and delightful but never knew were needed until their benefits were experienced directly.

Disruptors make the offer seem superior to all competing offers that produce similar results because they help redefine performance itself in Gamma. Disruptors are the principal means to shift your Angle of Attack down the Z-axis to a new definition of performance from the prior definition (P1), which is largely defined by the satisfiers and drivers in Alpha or Beta.

When an innovator creates a new performance definition as a Gamma, we refer to that new S-curve as P2 because it has disrupted the incumbents that expected to see competing offers that looked a lot like their own. Attracting initial buyers — even if you’re forced into giving away free samples when no one’s willing to pay — helps start this new S-curve sequence to improve your offer until the market defines a new Alpha as superior.

Finally, in Delta, think of new performance definitions as P(n) because there are an infinite number (n) of imaginary offer concepts in the minds of future innovators. Disruptors change how results are achieved by customers with the offers they have available. As discussed in the last chapter, our preferred way of sorting those changes is via the five dimensions of RECON (Risk, Efficiency, Customers, Outlook, Novelty).

How does the Angle of Attack of an S-curve relate to evolving superiority criteria by different buyer segments?

The improvement slope of Stage 1 in a new S-curve is more or less flat because the product has yet to perform well enough for any buyer to want it. In fact, the offer barely works at all! You might even experience slight degradation in performance since you’re tinkering with your offer to get that first sale.

However, as soon as you identify and integrate the right superiority criteria into your offer, your first buyer in the market will respond by rewarding you with a sale. This is helped in P1 by specializing in the performance drivers customer segments value most and minimizing the cost of over-delivering on satisfiers. You are the Beta that seeks to take customers away from Alphas at the low end of their performance curve.

Welcome to Stage 2!

As you identify and integrate satisfiers and drivers the market is telling you it wants more of, the slope of improvement in your offer’s performance grows vertically. As you continue up the hockey stick of improvement in Stage 2, new buyer segments demand more and greater performance, and they reward us with higher prices and fatter profit margins. You are taking these customers away from complacent Alphas that over-deliver on satisfiers but lack our specialized cost structure advantage to bring a more affordable solution to buyers.

Up-market competitors in higher tiers of performance willingly shed their least desirable customers to your superior drivers. As you bleed off more and more of their customer base, however, incumbent competitors will tend to overreact by mistakenly over-delivering on satisfiers in their futile attempt to protect dwindling market share. There are irresistible incentives for you to keep improving to continue taking share from Alpha incumbents. Fewer and fewer buyers exist up-market for your continually-improving offer.

But you are unstoppable. Profits continue to grow as your offer meets higher performance expectations while those customer segments are willing to pay more.

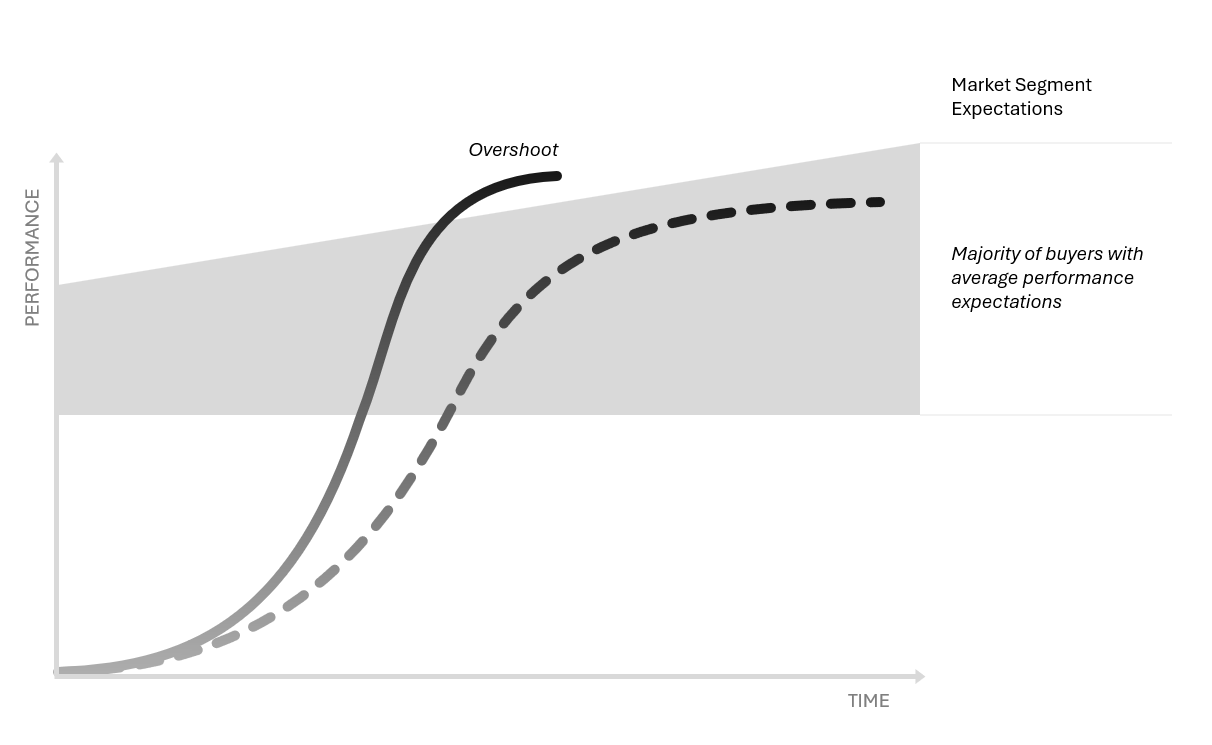

Even though the unit sales volume is no longer growing or might even be shrinking at this point, total revenue and net income grow larger and larger. This reflects the smaller number of more premium buyers at higher tiers of performance. You are entering the overshoot phase of Stage 2 when your Angle of Attack must stretch out its slope of improvement to match buyer expectations of improvement over time.

Welcome to Stage 3!

During Stage 2, the Angle of Attack of the offer has a much steeper slope than the Angle of Attack of expectations for improvement by the buyers in terms of offer performance. But once you’ve reached Stage 3 and achieved Alpha, trying to make your offer better yields fewer and fewer buyers. They lack the ability to appreciate the improvements you’re engineering into your offer. You might even see another Beta begin to take your customers away because your offer delivers more than what they want or need. Unfortunately, because they have pricing power to charge more, successful new Alphas tend to continue cramming more and more performance into their already successful offers.

This is the fatal mistake of overshooting.

Unit sales volume suffers as your cost structure escalates to satisfy these fewer and fewer, more demanding, but profitable buyers. The incentives are counterintuitive. If you wish to maintain your position at the top, you must lower the slope of your Angle of Attack relative to market expectations. The slope of offer improvement should match the slope of customer expectations, with an Angle of Attack of zero. You must resist the temptation to cram more unvalued performance into your successful offer, or you will exceed the highest performance expectations of buyers.

Figure 10: Stretching out Stage 2 improvements to delay Stage 3 Angle of Attack correction from overshooting can extend the profitable life of a new Alpha offer.

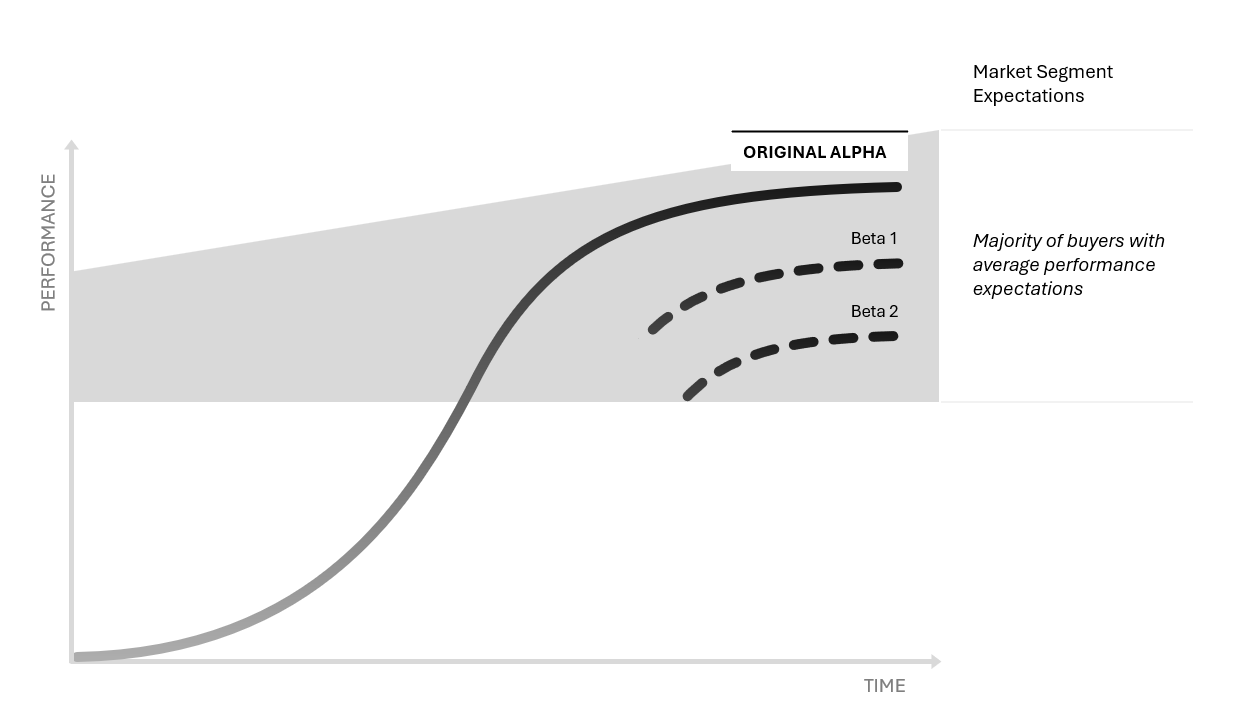

When you learn how to pull this off successfully as an innovator, you can maintain Stage 3 indefinitely. But you will inevitably ask yourself, “How can we ensure simpler, cheaper competitors won’t take share from all the buyers we’re still overshooting?”

The answer is to bring simpler, cheaper offers to buying segments down-market as a Beta to your Stage 3 Alpha. You become your own fiercest competitor in P1 but capture substantially more and more of the total available market share. You will also effectively crowd out specialized Betas before they can gain a foothold to support their competitive march up-market against your incumbent position.

Figure 11: As your original Alpha reaches Stage 3, you must lower the improvement slope to match the most demanding performance expectations. This creates opportunities for you to introduce Beta offers at lower performance tiers to prevent the introduction of competing Betas from other providers.

But what about disruptors?

Because customers and competitors determine satisfiers and drivers, most of your control over redefining performance will happen in Gamma (P2) through disruptor criteria you define and the market learns to accept. Stage 1 of a new Gamma S-curve means buyers can’t define what they need but will know it when they see it.

Finally, imaginary Deltas represent future S-curves down the Z-axis (P(n)). Just as Scottish weavers imagined a future where little dogs exterminated their rats for them, you can imagine wild concepts for offers no one might buy today, but which disruptor criteria eventually make irresistible.

Applied Case Examples

How do these three types of superiority criteria work across different industries? Do they work the same way wherever customer expectations reward the innovator who aligns their offer with the criteria the buyer will reward with share?

The humble light bulb is a simple example everyone is familiar with that proves these principles.

Incandescent bulbs sat at the top of the market for decades. Eventually, they lost ground to light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which have a much longer usable life and lower power consumption. The average number of hours of the lightbulb’s life redefined environmental sustainability as the driver for buyers.7

Incandescent bulbs were an Alpha so secure in their superiority they had grown comfortable ignoring competing offers — that is, until environmental sustainability challenged their superior position in the minds of buyers. Even if individual buyers preferred incandescent lighting, regulators governing environmental priorities exerted pressure on makers to switch to LED technology. Superiority criteria don’t always come from the buyer exclusively. The disruptor criterion of LEDs was the feeling buyers enjoyed of being more environmentally sustainable.

What usually happens with inexperienced Alphas is an overshoot, quickly followed by an overcorrection. Incandescent bulb makers, ironically, fit this definition of “inexperienced” because they had not encountered serious competition for their superior offer. Alphas continue engineering performance improvements, justifying the increase in cost structure under the assumption that the market will continue to indefinitely reward those improvements with even more profitable market share.

In reality, the up-market will inevitably grow so thin that there are no buyers left who can afford all the cost and drag associated with consuming the offer. The naïve Alpha will realize too late it must cut costs and reduce prices down-market to stop erosion to Betas. The Alpha will proceed to overcorrect its Angle of Attack to a negative slope, precipitating the offer’s Stage 4 decline.

General Electric experienced this situation with its consumer lighting business. Founded by incandescent lamp inventor Thomas Edison, GE had dominated the lightbulb industry for well over a century. It also had grown to become a leader in dozens of other businesses. But when Jeff Immelt became CEO in 2001, GE started rethinking its conglomerate approach and began trimming back non-core arms of the company.

In 2002, Immelt created a new unit — GE Consumer Products — to consolidate most of the company’s consumer businesses, including lighting and appliances. GE Consumer Products accounted for only 6-7% of GE’s revenue, and by 2017, the company’s consumer and commercial lighting business accounted for only 2%. Eventually, GE sold its consumer lighting business in a continuation of its overall shift away from consumer products. In the past few years, it has become focused on industrial products such as power turbines and aircraft engines.8,9

An Alpha might still continue to sell a declining offer to buyers who appreciate it for its nostalgic characteristics and tolerate comparative underperformance. As unit sales fall, the price continues to go up. But nostalgic buyers won’t care nearly as much about price. This counterintuitive incentive relationship can trick Alphas into retaining such attractive market segments for too long, as GE did with its light bulb business. Nostalgic buyers can keep a company in business, assuming that regulators don’t get in the way too much by enforcing new standards that directly or indirectly force a general phase-out, as the United States Congress did with incandescent light bulbs by setting new efficiency requirements.10 But the declining Alpha will experience increased vulnerability to the threat of competitors.

Another good example of nostalgia coming into play is acetate camera film. Some photography connoisseurs continue to enjoy this outdated technology despite the vast majority of photographs being captured digitally. Photographers who prefer film media will pay whatever the price is to acquire any of its declining supply. This phenomenon will incentivize specialist makers in Beta to invest in fulfilling these niche sales with increasing precision.

The same nostalgic economics ring true for vinyl record albums in the subscription music streaming era. If you enjoy a day on the water, you might prefer a sailboat instead of a pontoon. And, even though the smartphone in your pocket can connect you in real time with almost anyone on the planet, isn’t it nice to receive a handwritten letter from a friend?

Even when a new Alpha takes almost all the market share, hobbyist or nostalgic markets will emerge in Stage 4, demanding the old technology.

Pricing is one of the more difficult mysteries to get right in superiority criteria. Henry Ford provides an illuminating example of how pricing can become a disruptor criterion as Alphas and other competitors seek to gain or maintain market share.

Around the turn of the 20th century, car manufacturers were still experimenting with design, trying to build viable prototypes that were easy to reproduce. Ford experimented with many models, including the A, B, C, F, K, N, R, S, and — who could forget — the famous Model T. As he experimented, buyers responded better to Ford’s more affordable cars. Their response convinced Ford that he’d only succeed if he could move automobiles away from their position as a luxury item. As a luxury, cars were overshooting almost every potential buyer in the market. Buyers down-market needed a product that was cheaper, more versatile, and easier to maintain.11

The question for Ford was how to increase production efficiency to shave costs to improve affordability. He tested ways to accelerate work through his factory, including arranging parts differently on the shop floor and even dragging parts along on skids. Ford broke the assembly into 84 discrete steps and engaged one of the first management consultants, Frederick Winslow Taylor, to improve industrial efficiency. This work led to the development of the moving-chassis assembly line in December 1913, which was mechanized the following year.12

Ford’s assembly line meant that the automobiles he built were simple and uniform — each vehicle looked identical. This uniformity was the product of industrial efficiency, but it didn’t matter much to the market since affordability was the most valuable disruptor criterion to the average American consumer.

Ford’s competitor, General Motors, recognized that affordability also meant spreading out the cost of an automobile into a payment plan. GM focused on providing financing to car buyers. Eventually, the industry even offered leasing options to buyers who did not need title to the vehicle itself. Finding a way to fit an automobile into a middle-class consumer budget changed how buyers considered competing offers.13

Ford’s story is a good example of how superiority relates to the Control Factor Theory we introduced a couple of chapters ago. Ford foresaw a day when his cars were everywhere: “When I’m through, about everybody will have one.” Ford concentrated on industrial efficiency to attack the cost of production. This translated into the primary dominion control factor he knew the market would reward — affordability.

Assembling one of the most complex machines in human history meant simplifying the production system itself would yield the greatest leverage to reduce the cost of production. So, Ford’s linchpin dominion factor was reducing assembly to 84 steps by training each worker to specialize in only one step.

The key to achieving Alpha is that superiority happens by choice, never by chance.

Superiority involves intentionally shifting your mindset to focus only on factors you can control and deliberating how to take action on them. This inventory of the factors under your exclusive governance will direct resource allocation decisions more precisely and sequence your priorities with higher resolution.

Roger Martin and A.G. Lafley emphasize this principle in their bestselling book, Playing to Win, How Strategy Really Works.14 They describe strategy as “a set of interrelated and powerful choices that positions the organization to win.” They present a strategy choice cascade with five key questions:

What is our winning aspiration?

Where will we play?

How will we win where we have chosen to play?

What capabilities must be in place to win?

What management systems are required to ensure the capabilities remain in place?

As the innovator, only you have dominion over each of these five choices, and the order of the choices matters.

How-to-win comes after where-to-play because winning in one segment could be radically different from winning in another. And sequencing is critical because your study of characteristics for how-to-win in an adjacent market might be exploitable in other where-to-play segments.

Although this process is a simple one, most leaders don’t do it very well.

Management tends to concentrate on capabilities and managerial systems without regard for where to play or winning aspiration, assuming those choices are seldom up for debate. They assume that the inertia that has carried their success to the present will likely persist in perpetuity. They also assume their mission is only to engineer incremental improvements each year.

More complex engineering problems make for more problematic narrowmindedness. Commitment bias is one of the most powerful human delusions. We grow complacent about reconsidering big macro-environmental changes since we are focused so intently on resolving the complex problems in front of our face.

Inevitable mistakes, which will affect your right to win in the market, happen when you make decisions caused by irrational emotions. Superiority is in the eye of the beholder. You take share only to the extent that the market agrees you are worthy of it. You make a winning choice by complying with the superiority criteria or innovating on a way to disrupt it.

The culture of your buyers will impact how you define your job-for-hire. Let’s look at the examples of three specialized fitness competitors — Concept2, Peloton, and CrossFit — to reveal how buyer culture relates to superiority criteria.

Concept2 targets specific athletes, especially rowers. Most rowers prefer to be on the water rather than a machine. But Concept2 ergometers fill the gap for crew teams that can’t train when rivers and lakes freeze over, keeping rowers fit and ready for the spring racing season.

The core technology differentiator of the Concept2 “Erg” is the resistance flywheel that replicates the friction drag effect of moving a boat through water. A performance-monitoring computer measures the athletic effort required to defeat that friction.

Coaches discovered ergometers mimicked the real thing well enough to evaluate rowers for seat placement in the boat over the winter training season. Eventually, the majority of coaches came to use Concept2 equipment to maintain the physical conditioning of their crew teams, which helped the business dominate its relatively small market.

To grow beyond rowing, Concept2 recognized adjacent markets that might benefit from similar offers — specifically, cross-country skiing and cycling. To provide a value similar to what rowers would experience over winter, Concept2 developed the SkiErg and BikeErg. Skiers and cyclists wanting to keep fit when they can’t do the real thing outside found this modified ergometer equipment to be an offer they didn’t know they needed.

Concept2’s technology provides a physically similar approximation of athletic effort to defeat resistance drag in these otherwise dissimilar real-world sports. Concept2 might continue to develop new versions of the Erg for other sports where friction is defeated through cardiovascular strength. These innovation opportunities might be based on an athlete’s need to train in the off-season, often without teammates, or when otherwise unable to access their sport’s typical competitive conditions.

Then there’s the camaraderie of team sports itself, largely absent from solo fitness pursuits. When athletes can’t train together, online communities offer the connection they crave. While rowing can be a solitary sport, “spinners” value the atmosphere of a gym experience. The social elements of going to a gym are impossible to mimic digitally. But Peloton boomed when the COVID-19 pandemic closed most spin clubs and classes were forced online.

Peloton had the right offer at the right time as the macro-environment shifted; sales surged 172 percent in 2020.15 However, the mistake Peloton made — assuming the spike in demand would continue forever — contributed to a swift decline.16 This reversal was predictable, representing the classic fall of an Alpha that takes superiority for granted and overshoots Stage 3 up-market into tiers of demand with insufficient buyers to support their cost structure.

CrossFit attracts fitness fanatics to test their limits and push beyond them, energizing others to do likewise. Spotting another athlete as they max out a personal best also translates when Crossfitters are on the road looking to work out with a local box. The joy of high-intensity interval training has deep social togetherness aspects. For example, the “Murph” has become a CrossFit Memorial Day tradition honoring U.S. Navy SEAL Lt. Michael Murphy, who was killed in the line of duty in Afghanistan in 2005. Individual strength and endurance training is made into a team sport when we’re all maxing out on the same workout together.

All three companies target athletes with different definitions of personal fitness. The culture of each sport is a differentiating ingredient in each company’s value proposition. Because their customer segments define performance optimality using different superiority criteria, each company achieves Alpha in its own unique way.

Pumping iron in a weight room is a different gym culture than CrossFit. Cranking out ergometer workouts alone in your basement can’t replicate the team dynamics of rowing on the water with your crew. And when spin class is canceled for a year, how will you get motivation from a group of other cyclists pushing up a virtual Alpine mountain road?

Each company has a range of offers that satisfy, drive, and disrupt the expectations of its chosen market segments. Past success charts a path toward future innovation. When circumstances change, superiority criteria change with them. Adaptability of the offer sustains long-term competitive advantage. Occasionally, competitors learn from one another. CrossFit, for example, embraced the Concept2 ergometer as the optimal, full-body cardiovascular exercise with comparably measurable performance statistics.

What do fitness brands have in common with wristwatches?

For the past hundred years, automatics have been the beating heart of the wristwatch market. The power source for an automatic wristwatch comes from a rotor that spins with the motion of the user’s arm to wind the mainspring. As long as you move your arm, the mainspring winds itself. It’s pretty efficient technology, keeping accurate time to within plus-or-minus ten or fewer seconds per day.

But before automatic rotors made manually winding the mainspring obsolete, most used the same mechanical winding principle present for decades in pocket watches. Indeed, the first wrist-worn watches were simply pocket watches with lugs soldered on for a strap. These were innovated in the trenches of WWI Europe and enabled the wearer to keep their eyes fixed on the path ahead, scanning for enemies, without fumbling to see if they were still on schedule.

In 1969, Japanese watchmaker Seiko introduced the world’s first quartz-powered wristwatch, the Quartz Astron.17 Like all quartz watches do today, this timepiece relies on a battery for power. The battery sends electricity through a circuit that includes a quartz crystal, which serves as an oscillator. The circuit counts the vibrations, which occur at a specific frequency, and generates an electric pulse based on that count every second. Those pulses then drive the motor that controls the watch hands, displaying the time to the wearer.18

The Astron was 100 times more accurate than any other watch, to within five or fewer seconds per month! Its battery also ran for a full year, about 250 times longer than most mechanical watches that weren’t self-winding automatics.

This innovation represents a shift from P1 to P2, with the quartz crystal enabling a disruptively greater degree of timekeeping accuracy. However, changing the battery on a quartz watch is still a hassle. For the inexperienced quartz watch wearer, it often involves a visit to a jeweler.

Solar quartz watches, which use photovoltaic cells for power, were still in Delta during the initial introduction of quartz timekeeping. Solar quartz technology moved from Delta to Gamma in the 1980s as watchmakers brought their first offers to market. The battery in a solar quartz watch is permanent and doesn’t require the help of a jeweler to be changed every year.

Ironically, rotors were added to quartz watches in recent years to make battery recharging as automatic as mechanical watches can be through the motion of the wearer’s arm. This adaptation feels inevitable in hindsight, given that the parameter of battery charging became the differentiating driver of the quartz offer category.

Today, watch enthusiasts diverge based on the driver criteria most important to them. Most watch enthusiasts are very brand-specific, with the brand itself serving as the primary driver of their superiority criteria. Omega buyers might cross over to Rolex, and Breitling buyers occasionally defect to Seiko, but the differentiating criterion is how wearing a particular brand makes you feel. Rolex is synonymous with personal success, for example, so rocking a Rolex Submariner or GMT exudes a certain air of exclusivity and attitude for the wearer.

For buyers with a job-for-hire of knowing the exact time, every day, without resetting their watch for months or years, a quartz movement will be necessary. They also tend to be less brand conscious. This contrasting chronological accuracy of quartz with the brand superiority criteria of mechanical watches shows the differences of appealing to the desires of buyers. Some seek rare objects unavailable to others — like a Rolex Cosmograph Daytona or your grandfather’s pocket watch, which makes you think of him every time you look at it. Others simply want a tool engineered to exacting standards.

Sometimes, scarcity is the principal driver. One-of-a-kind timepieces can carry price tags over $1 million.19 Wearing a Richard Mille is more about showing off than it is about accuracy. With a price range hovering between $10,000 and $100,000, Rolex is the most valuable watch brand in the world specifically because not everyone can sport a Sub or Skydweller on their wrist.

A wearable status symbol is a different criterion than most mechanical watch hobbyists demand, especially when an Apple Watch or Garmin smartwatch has infinitely more utility than mere time-telling. Much like a sailboat, vinyl record collection, or film camera, the engineering nostalgia of a bygone era is the main reason to buy, and brand legacy is what most differentiates one watch from another.

Markets need time to accept new offers and reset baseline expectations for superiority in each segment. Remember that your definition of a satisfier, driver, or disruptor is fluid. A driver for one person might be a satisfier for another, and when enough of these criteria cluster together, there’s a new business waiting to be launched. This is how more than one company can hold a significant share within the same market.

As with a Rolex, the performance criteria of buyers often comes down to the scarcity of the brand itself. Branding often signals that superiority criteria of the market segment has lost an appreciation for other differentia between offers. Satisfiers can become obsolete over time, too. As buyers acclimate to an innovation or disruptor and the market saturates, that disruptive innovation can become the new minimum performance standard everyone will expect as a satisfier.

Finally, disruptors with staying power will shift the definition of performance into Stage 1 of a new S-curve. For example, the Apple Watch puts most of your iPhone’s value discreetly on display with a twist of the wrist, rather than forcing you to fumble for a slab of glass in a pocket or handbag. However, Rolex — not Apple — is the most popular luxury watch brand in the world because they reinvented the definition of performance for mechanical wristwatches.20 A Rolex, the status symbol, with its fine Swiss engineering of an automatic movement, is recognizable anywhere in the world and elevates the buyer’s status with it in ways Apple can only dream of.

Rolex is as Mercenary as they come, not only charging a small fortune for their lowest-end timepiece, but often making buyers wait years on the infamous Rolex waiting list to finally have the one they want allocated to them. It can take up to five years for a Daytona or GMT Master II to find its way onto your wrist. And just as you’d expect from a Mercenary, some Rolex Authorized Dealers (ADs) are known to encourage buying easier-to-find models to shorten your time in purgatory for the one you really want by establishing a relationship with them.

Superiority criteria for a buyer can be very inflexible unless their criteria changes, usually because a disruptor altered that criteria. Many first-time Omega Seamaster buyers gave up waiting for a Submariner and decided to try something different. If you’re an Alpha, you must resist the temptation to grow overconfident in the perpetual superiority of your offer, since Betas, Gammas, and Deltas are patiently waiting for you to do exactly that.

Which mindset is strongest in you?

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder." — Margaret Wolfe Hungerford (aka The Duchess)

Thinking back on the concepts covered in the first phase of the Insights-to-Action Supercycle (under-certainty, stochasm, and control), Discovery enables you to encircle your landscape and discard irrelevant uncontrollables. That boundary allows you to ignore whatever is outside the macro-environmental box you made to contain the contingency factors you must survive. Disruption (Chapter 4) is about seeing the frailties in existing landscapes and predicting how Angles of Attack will forecast the outcome of competitive battles.

In this chapter, Superiority, you align your offer to exploit those frailties or openings by obsessively consenting to whatever satisfiers or drivers the market will telegraph to you. You look for the potential to redefine performance with disruptors nobody knew they needed until they noticed yours. It’s up to you to make sure that your offer stays in perfect alignment with that gradually sloping curve of market segment expectations, even when your engineering department is screaming they need to make your offer better and better.

Mercenaries are great at competing on satisfiers and drivers. But they generally struggle when competing on disruptors. They’re more concerned with gaining the immediate financial rewards of taking share from someone else than they are experimenting with creating new markets where no prior signals indicate a market exists.

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and it may be necessary from time to time to give a stupid or misinformed beholder a black eye!” — Miss Piggy

Alphas struggle the most with delaying more immediate gratification to develop disruptors that redefine performance as a Gamma. Gammas put incumbent Alphas and Betas at risk of irrelevance and generally cannot survive the corporate immune system inside an Alpha. Alphas prefer instead to acquire smaller innovators who have succeeded experimenting with early-stage investor capital.

The advent of corporate venture capital — such as the venture arms of Google or Intel in tech, and Novartis or J&J in biohealth21 — recognizes this frailty in large enterprises. Corporate VCs use the Alpha’s excess capital to foster disruptive innovation in markets its shareholders might find puzzling or threatening. These markets, however, could unleash the next faster-growing market segment if they can buy right of first refusal and gain exposure to the risks and rewards of those innovators in exchange for their investment. The recent rise of Generative AI threatens every business Silicon Valley has succeeded with so far. For Alphas to put GenAI apps to work reinventing themselves, they must partner with Gammas and Deltas innovating unthinkable changes to our technological future.

Do you think of yourself as the Mercenary Alpha or Beta taking share from other Mercenaries? Or, are you the Missionary Gamma or Delta creating new markets and making incumbents irrelevant?

The reason we wrote this book is to equip you with the versatility to be both whenever circumstances demand.

Now, let’s look at how Starbucks shows this versatility in action. A Missionary mindset can eventually win the war for market share, but you’ll require a Mercenary CEO to do it.

When Starbucks started out in 1971, it was just a coffee shop in Seattle. Howard Schultz joined the company in 1981 when there were only four such coffee shops, but he was already percolating the idea of selling premium coffee across the country. After serving as head of retail and marketing for the company, Schultz resigned over disputes about how to expand. However, in 1987, he bought the business for $3.8 million and took the company public in 1992 before going international in 1996.22

Schultz’s vision was to provide a better coffee experience, including a unique atmosphere that would produce positive emotions different from the emotional response prompted by home or work. How better to enjoy a coffee than while reading a good book or magazine? This kind of atmosphere encapsulates the Third Place — a “warm and welcoming environment where customers can gather and connect”23 — so important to Starbucks' disruptive potential as a Missionary.

To build his vision and expand the company, Schultz was the perfect Mercenary. He sought out locations with greater traffic potential and joined forces with other established Alphas in adjacent markets. Bookstores such as Barnes & Noble became cornerstones of the company’s Third Place strategy. However, Schultz’s Mercenary instincts focused on financial performance and taking share everywhere Starbucks opened a store.

When the business began to struggle in 2008, Starbucks ignored short-term shareholder priorities. Schultz sacrificed expansion to refine product merchandising alignment with actual customer preferences. This included skilling a workforce to make the coffee outing pleasurable again. Schultz’s Mercenary consented to the Missionary innovation that would restart Starbucks’ growth.

It took 14 years for Starbucks to succeed in Seattle and decades more to expand worldwide. In co-founder Zev Siegl’s words, Starbucks is “a slowpoke.”24,25 But Schultz’s Mercenary instincts catapulted the company to the financial success shareholders would approve of.

Starbucks succeeds in the long run by patiently adhering to market superiority criteria that rewards the company with growing share. While patience in creating the Third Place might be Starbucks’ most Missionary characteristic, the Mercenary alone consents to the market’s definition of satisfiers and drivers.

How does it make you feel when you need a coffee and notice a Starbucks logo just down the street? The woman in the logo is called “The Siren” and is no ordinary mermaid. The Siren calls out to you. Her beauty is driving you to satisfy your most fundamental needs for caffeine or a tasty snack. The next time you see a Starbucks Siren, notice her two tails and remember the Missionary and Mercenary mindsets she represents.

Memoirs

In January 2001, about two years before we started working together at Aurora, our mother fell down the stairs and broke her hip. She’d lived alone in the Chetek, Wisconsin home where we grew up — and she had too — since Dad had passed two years earlier, and she was suffering from COPD. She most likely tripped on the supply tube from her oxygen tank.

As we visited with her after her hip repair surgery at Rice Lake Medical Center, we did our best to keep things upbeat. We chuckled as Mom, doped up on painkillers, mistook the red light of the oxygen sensor on her big toe as the ember of a lit cigarette and tried to reach for a puff.

The situation was serious. Some 25 years earlier, her mother had fallen down the same steps, broken her hip, and died not long after. The sad but poetic parallel with our mom’s condition might have led her to realize her own life might be coming to an end, too.

We needed to figure out where Mom would call home during her recovery since neither of us had the right circumstances to care for her in our own homes. She certainly couldn’t stay alone in hers in this condition.

We started to look at nursing facilities in the area, including one just blocks from the hospital in Rice Lake. We considered the obvious criteria for finding her a new place to live, such as the cost of care and the vibe we got from staff and residents.

One important driver we overlooked was her need for friends and companionship. When we discovered how important social connection would be for her recovery, the only option was to bring her home to Chetek. Knapp Haven was home to many ladies she’d worked on her whole beauty career, visiting weekly to help them look better than they felt living in a nursing home. Perhaps the end of her life would come in the same place where she had spent so many days loving others through her calling as a beautician.

Just four months after settling in, she fell again and broke her other hip. While her doctor was able to replace that hip as well, a routine scan revealed a spot on her lung — cancer. When it moved to her liver, the end was near. When we asked where she wanted to be in her final days, she said, “I want to go home.” With hospice attending to her daily needs, we scheduled our days at her side, until a few weeks later, just five days before 9/11, she passed in the comfort of her living room, surrounded by friends and family.

While Dad’s passing was sudden and unexpected, Mom’s death was something we could see coming. It prompted us to find new ways to work together. We had to sort out which of us would take the lead on each priority for decision-making, as well as how to act on her behalf in her final days.

You’ll surely encounter situations where you are forced to make major decisions that will profoundly impact someone you love, your community, or maybe even the world. Your Mercenary will tempt you to focus on immediate, practical priorities for you and the other stakeholders involved. Instead, humble yourself to put others’ interests ahead of your own by empathetically seeing beyond your own collective satisfiers and drivers.

Let your Missionary gain an appreciation for others’ superiority criteria to reveal potential disruptors. When you stand up for those who cannot stand up for themselves, you can consider what’s best for someone who might never do the same for you. The Missionary expects no quid pro quo like the Mercenary would. The Missionary serves a higher calling.

Growing up as boys together, we were differently gifted and naturally drawn to different interests. Arik was a bit of a mama’s boy and was driven by manipulating the world around him. This meant endless learning opportunities but few worldly rewards. Just as our mom’s inner Mercenary supported our dad’s Missionary attempts to explore new ventures, her instincts also supported Arik’s curiosity to discover his calling in life by exploring mysteries until he found the one that made him happy.

Derek was our dad’s shadow. He took great joy in father-and-son activities, particularly anything mechanical or engineering-related. That drive proved to be mutually beneficial to our dad, as it allowed him to fulfill his Missionary need to guide and teach.

We each had different definitions of what would satisfy and drive us. We could lean on both of our folks, but we were drawn to the parent who complemented our strengths the most. As we matured, they filled in the gaps where we were weak. Dad’s Missionary was the necessary element best able to meet Derek’s interest in exploiting systems to their maximum ability. Mom’s Mercenary was the missing ingredient balancing Arik’s drive to explore things he knew nothing about and might never benefit from.

In 2009, Roger Martin’s The Design of Business helped Arik finally internalize how innovation works.26 The book outlines why companies seldom realize optimal financial results when they try to innovate — they misunderstand the relationship of knowledge, growth, and the role of design thinking. Design thinking centers on the unmet needs of the customer, whether the customer recognizes the need or not.

Much like the young brothers complementing their parents' inherent gifts — and vice versa — design thinking integrates the knowledge needed to innovate new solutions and maximize their performance.

Innovation begins when we explore a mystery in the world without having an explanation or understanding of it. Out of Missionary curiosity, explorers manipulate that mystery to figure out what makes it tick and how to produce value from various rules governing its validity. Eventually, if another mystery doesn’t steal the explorer’s attention, they’ll discover many valid ways of manipulating the mystery. When the most valid way is discovered, a heuristic is born to govern how other people use their knowledge of the mystery to exploit the value it produces in the market.

Heuristics then concentrate on reliability to maximize the value produced. This is usually accomplished by gradually removing as many human interventions as possible since they might lead to costly errors. When the humans are all gone, human errors go with them, and we turn our messy heuristics into a near-perfect algorithm.

An algorithm develops ways to automate until, at the very end of the knowledge funnel,27 they are eventually codified into software, which no longer requires human intervention at all. Code is infinitely exploitable and the cost of production for the value it creates is miniscule by comparison.

Figure 12: Mysteries are explored until they have been sorted into heuristics for manipulation in valid ways by humans. Heuristics are further refined into algorithms that can be exploited for profit by gradually removing that human intervention to make them perfectly reliable.

Elimination of human involvement will continue until all manual effort has been removed by codifying algorithms into computer code which is perfectly reproducible at essentially zero cost. This code remains stable until it is rendered irrelevant by changes in the macro-environment itself.

This principle holds until the landscape changes and the algorithm is made obsolete. Obsolescence of algorithms is inevitable and precisely how successful enterprises eventually fail. When incumbents ignore new mysteries, they fail to derive valid, new heuristics or codify reliable, new algorithms for their next business. They also fail to regenerate the institutional knowledge of how to innovate in the first place.

Arik’s realization of how these forces were working inside Aurora created a sense of urgency around Derek’s transition to CEO in late 2009. Martin suggests the way for leaders to work together more successfully is to intentionally practice their weakest attributes — explorers must emulate how to exploit and exploiters how to explore. Arik was more naturally drawn to new mysteries, much the same way Derek’s work focused on perfecting heuristics into algorithms. Arik moved into an R&D role looking specifically at the persistent mysteries of the intelligence and insights world, while Derek concentrated on maximizing the value of our incumbent businesses.

The book you’re reading right now is an example of this phenomenon. Had the CEO transition not happened, you wouldn’t be reading about under-certainty, stochasm, Control Factor Theory, Angles of Attack, or superiority criteria because Arik wouldn’t have had the intellectual space to develop the concepts. But without profitable algorithms to fund our growth, the company wouldn’t have had the free cash flow to invest in those innovations.

We’re obviously not saying that humans have no value — after all, Aurora aspires to be The Human Intelligence Company. The fact is, humans are most necessary pre-algorithm, when imperfect processes are not yet thoroughly validated and when unresolved heuristics remain unreliable. A perfectly codified algorithm operates without human direction, intervention, or correction. But humans become essential once again when every algorithm inevitably grows obsolete because its landscape has changed. When this happens, humans are the only ones who can choose which new mysteries will regenerate innovation opportunities into a new business.

Our podcast, Running Into The Fog, is another example. We developed the show as a result of recommitting ourselves, during the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, to be a little more like each other every day.

Years before control factors became a theory, Arik had the chance to validate his hypothesis about KITs really being about control with a colleague many years his senior, Jan Herring. Herring is credited with adapting Key Intelligence Topics and Questions (KITs/KIQs) from CIA to CI during his time at Motorola. Although he’d worked with clients for a couple decades, over dinner at a Council of CI Fellows annual meeting, Arik confessed to Jan he’d never seen Key Market Players done well in a CI program setting. Most of the time, it seemed to default to a company profiling exercise thrown together in PowerPoint decks.

Arik questioned whether KITs was less about competitors’ topics and questions and more about influencing the control factors of others in the landscape. Herring agreed it would make more sense to think of it that way and Arik started work on Control Factor Theory.

Briefings, boundaries, and memorable keynotes

In 2005, I attended the Product Development and Management Association (PDMA) conference in San Diego. While I was there, I saw Michael Treacy deliver the keynote speech. Treacy is best known for his writing on topics like how companies achieve double-digit growth and maintain the discipline of market leadership.

In 2009, I was chair of the Strategic and Competitive Intelligence Professionals (SCIP) annual conference in Chicago. I accepted the role with one condition: Michael Treacy would be our headliner. With his PDMA keynote in the back of my mind, I went to Natick, Massachusetts to interview him. He agreed to do a private luncheon with 10 of our top sponsors and their guests, which created a first-of-its-kind event at SCIP’s conference.

Treacy appealed to me as a keynote speaker specifically because he helped me understand that market leadership (superiority) is not something we define except through our actions as Missionaries and Mercenaries. But the audience remembered him for the same reason Clay Christensen was memorable at the 2006 conference that Arik had chaired.

Because we both spent a day briefing each of our keynote speakers, Christensen and Treacy put well-defined boundaries around the landscape of remarks they would share during their speeches. Alongside targeting the specific needs of competitive intelligence professionals, this focus made them memorable for conference goers when deciding whether to return to future SCIP conferences. Since then, we’ve used the same technique in preparing headliners for other events to resonate with their audiences.

— Derek

Questions to Activate Superiority

Congratulations on reaching the penultimate step in Optimality, where your offer’s superiority criteria has been deliberately chosen from satisfiers, drivers, and disruptors that the market will reward with share. Through the final step in this process (see Chapter 6: Humility), you will derive an investment-grade conjecture (IGC).

You’ll notice the questions to activate superiority are treated a little differently than in the other chapters. This is because the questions must all focus on market segment buyers and the stakeholders who serve them, and not nearly as much on your own operating parameters.

Your IGC is the version of your offer you can test against the influence factors of other stakeholders — especially buyers — who might help or hinder your success during the final phase of the Supercycle. We call this final phase Simulation because imagining how others will react is the easiest way to gain an emotional appreciation for everyone else’s feelings about your innovative new offer. Simulation is where influence control factors are pinpointed, as reflected in the memoir above with Mr. Herring’s acknowledgement that Key Market Players is actually about influencing others’ impact on your strategy.

Considering the complexities of this sequence and all the information flow culminating in this chapter, we’ve built the Superiority Criteria Canvas below to ensure you have all the ideas top of mind as you get started. This tool is designed to help clarify an offer that will be regarded as superior by your market segments and allow you to summarize everything you’ve discovered about your superiority criteria. You might even use it as a cover sheet for an IGC being presented for funding to keep top-of-mind your rationale behind resource allocation decisions.

Figure 13: The Superiority Criteria Canvas helps inventory the criteria your market segment(s) will reward with share and begin to ask questions about how other stakeholders will react to your offer.

The top half of the canvas clarifies the market segments in which you’ll play and adjacent segments you could explore later for market entry. Outlining the pros and cons of satisfiers and drivers as defined by those selected segments will help financiers understand what you will need to control or cope with to ensure superiority remains intact.

The bottom half of the canvas allows you to break out the unexpected role disruptor criteria will play in market segment preferences (RECON — see Chapter 4: Disruption). The first two dimensions, risk and efficiency, focus on the cost-compared value a naïve buyer will be surprised with and which they never expected an offer to supply. They work together to change how the buyer appraises the value of the offer. The remaining dimensions summarize where you’ll play and how your market segments will clarify your truly new differentiators to redefine performance in Beta, Gamma, or Delta.

Counterintuitively, the spaces on the canvas for helpful and hostile responses are not meant to summarize whether other players in the market will help or hinder you, but whether those other players see you as helpful or hostile to them. In other words, it’s about anticipating their appraisal of your offer relative to their own, rather than obsessing over yours. Trying to see yourself through competing or allied eyes is important because it encourages the kind of empathy you’ll need to survive in the long run.

Your Missionary must empathize with other stakeholders because it’s difficult to accurately assess why those stakeholders might view your offer as having a negative or positive impact on their self-interests. The Mercenary purpose of caring what they think is not to appease them, but to influence them to help you win.

The under-certainties section at the bottom of the canvas is where you outline which questions must be answered to determine whether stakeholders might be helpful or hostile to you. This outline includes the potential actions other stakeholders might take in response to your offer and the kinds of questions you will have to answer before Simulation:

How will different types of stakeholders respond to the offer you’ve brought into the market?

How will incumbent competitors defend their market share from your new offer?

How will your target customer segment react?

Will suppliers, regulators, and other stakeholders help or hinder your new offer taking share from incumbents?

Most business leaders struggle with Missionary humility because of the culture of short-term financial performance we’ve become so obsessed with in business. Few have ever been taught how to be simultaneously idealistic and pragmatic like you’re learning to do reading this book. Mercenaries mistakenly assume they cannot achieve superiority while considering the interests of others at the same time. The business world has incentives that reinforce this mindset and seldom encourage leaders to think beyond ROI.

“There is nothing noble in being superior to your fellow men. True nobility lies in being superior to your former self.” — W.L. Sheldon

Remember, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. It's never you defining your superiority; it’s your customer telegraphing which criteria they will reward. The choice is yours whether you obsessively consent to that criteria or not. And if you do not consent, you must then choose to redefine that criteria with disruptors in order to win.

We have learned that humility — thinking of others first — paves the way for sustainable innovation. As you prepare to simulate your plans, try to put others’ interests ahead of your own. In our next chapter, we’ll explain why humility doesn’t diminish you. In fact, it might be the one thing that takes you to the top.

References:

Wiktionary, “Uneducated guess,” accessed January 1, 2024 https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/uneducated_guess#:~:text=uneducated%20guess%20.

Innobatics, “The Four Stages of Learning,” accessed January 1, 2024 https://innobatics.gr/en/learning-stages/#:~:text=In%20the%20initial%20stage%2C%20the,deep%20in%20the%20Amazon%20Forest.

Therapist.com, “What is the Dunning-Kruger effect?,” September 12, 2024 https://therapist.com/behaviors/dunning-kruger-effect/.

Cambridge Dictionary, “Educated guess,” accessed January 1, 2024 https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/educated-guess.

Denise Flaim, “Yorkshire Terrier History: From Working-Class to Luxury Lapdog,” American Kennel Club, March 8, 2021, https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/dog-breeds/yorkshire-terrier-history-toy-lapdog/.

Ovidijus Jurevicius, “VRIO Framework Explained,” Strategic Management Insight, August 16, 2022, https://strategicmanagementinsight.com/tools/vrio/.

Rebecca Matulka and Daniel Wood, “The History of the Light Bulb,” Department of Energy, November 2023, https://www.energy.gov/articles/history-light-bulb.

Dana Mattioli and Thomas Gryta, “General Electric Wants Out of the Lightbulb Business,” The Wall Street Journal, April 5, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/ge-weighs-sale-of-consumer-lighting-business-1491415326#google_vignette.

Warren Schoulberg, “GE Unplugs From Its Last Consumer Products Business With Lighting Sale,” Forbes, June 1, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/warrenshoulberg/2020/06/01/ge-takes-the-life-out-of-the-company-with-lighting-sale/.

“DOE Finalizes Efficiency Standards for Lightbulbs to Save Americans Billions on Household Energy Bills,” U.S. Department of Energy, April 12, 2024, https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-finalizes-efficiency-standards-lightbulbs-save-americans-billions-household-energy.

“History of the automobile,” Britannica, accessed January 31, 2023 https://www.britannica.com/technology/automobile/Ford-and-the-automotive-revolution.

History, “Ford’s assembly line starts rolling,” A&E Television Networks, November 13, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fords-assembly-line-starts-rolling.

“General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC),” The Crittenden Automotive Library, accessed January 31, 2023 http://www.carsandracingstuff.com/library/g/gmac.php.

Roger Martin, “Strategy,” Roger L Martin, Inc., accessed January 31, 2023, https://rogerlmartin.com/thought-pillars/strategy.

Jordan Valinksy, “Peloton sales surge 172% as pandemic bolsters home fitness industry,” September 11, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/09/11/business/peloton-stock-earnings/index.html.

Laura Entis, “Peloton Thrived in the Pandemic. Now What?,” March 9, 2022, https://www.outsideonline.com/health/training-performance/peloton-pandemic-fitness-company-future/.

Seiko, “Our Heritage,” accessed December 24, 2022, https://www.seikowatches.com/us-en/special/heritage/.

“Here’s How a Quartz Watch Works,” Hamilton Jewelers, July 17, 2018, https://www.hamiltonjewelers.com/blog/2018/07/17/heres-how-a-quartz-watch-works/.

Andrew Neita, “Richard Mille Watch Prices: Complete 2023 Price List & Investment Guide,” Wrist Advisor, December 24, 2021, https://wristadvisor.com/how-much-is-a-richard-mille-complete-pricing-guide/.

SwitchWatchExpo, “The Most Popular Luxury Watch Brands,” The Watch Club, accessed September 15, 2024, https://www.swisswatchexpo.com/thewatchclub/2023/06/01/most-popular-luxury-watch-brands/.

CBINSIGHTS, “The Top 20 Corporate Venture Capital Firms,” April 16, 2018 https://www.cbinsights.com/research/top-corporate-venture-capital-investors/.

Starbucks Stories & News, “Howard Schultz,” Starbucks, accessed January 1, 2024 https://stories.starbucks.com/leadership/howard-schultz/.

Starbucks, “Third Place Development Series,” Starbucks Global Academy, accessed September 22, 2024, https://starbucksglobalacademy.com/third-place/.

Christian Mangold, “The Starbucks Company. Success Strategy and Expansion Problems,” 2010, https://www.grin.com/document/159596.

Natalie Gerhardstein, “Starbucks was a ‘slowpoke’ by today’s standards: co-founder Zev Siegl,” September 25, 2019, https://delano.lu/article/delano_starbucks-was-a-slowpoke-todays-standards-co-founder-zev-siegl.

Roger Martin, “The Design of Business,” Roger L. Martin, Inc. (‘RLMI’), accessed February 4, 2023 https://rogerlmartin.com/lets-read/the-design-of-business.

Roger Martin, “Chapter One: The Knowledge Funnel: How Discovery Takes Shape,” Thinkers50.com, accessed February 4, 2023 http://www.thinkers50.com/book_extracts/martin.pdf.