Chapter 8: Empathy

How understanding the feelings of others - better than they know themselves - energizes your insights to make action irresistible.

“Before you criticize a man, walk a mile in his shoes. That way, when you do criticize him, you’ll be a mile away and have his shoes.”

— Steve Martin

What will I learn in this chapter?

You’ll discover why empathy — the ability to understand the feelings of others — is essential for confident action and negotiation with partners and even competitors. You’ll connect empathy to its precursor traits of humility and guile to better assess your ability to endure misleading, vague, abstract, troubling, or uncertain obstacles on your journey to superiority.

Here are your key takeaways:

Empathy is the desire to care about and understand the feelings, thoughts, or experiences of others in a way that helps you explain how they are acting and how they’re likely to act next. Understanding others also helps you to act in the best interests of your partners and friendly stakeholders, rather than only in your own interests.

Empathy is different from sympathy. Sympathy is an acknowledgment of another’s experiences that does not require you to have experienced the same thing. Empathy suggests you’ve felt the same way they do at some point and can anticipate their reactions based on your own past actions.

Most intelligence analysis ends up being less predictive than it is palliative; it helps stakeholders to feel better even though circumstances might be grave.

Gradually exposing stakeholders to the cold, hard truth without an appreciation for how they’ll receive it can cause a reaction, not unlike an immune system response, that is often damaging or even terminal.

Empathy helps us see the extraordinary in the midst of the ordinary. Hope is the uniquely human characteristic necessary to sacrifice suboptimal options, which excludes all but the winning choice.

We’ll look at examples ranging from cinema, banking, wargaming, childhood allergies, and coping with the death of beloved parents, to overcoming channel conflicts and how the Ivy League adapted to online learning.

Doctrine and Tradecraft

In 1945, Paramount released The Friendly Ghost, the cartoon that first featured the protagonist Casper. In the cartoon, Casper is surrounded by other ghosts who only want to scare the living.

Casper, who is much kinder and gentler than the other ghosts, feels alienated by anyone who might accept him. He is so repelled by this that he packs up his few belongings and leaves. But each time he tries to make friends — predominately among the living — he scares away everyone he meets. Around six minutes into the cartoon, he gets so depressed and despondent in his deep loneliness that he tries to lie down on a railroad track, hoping to do away with himself. Of course, ghosts can’t die, and the passing train doesn’t hurt Casper at all.1

Why is it so easy for us to relate to Casper’s predicament? Having felt rejected ourselves — years ago at recess or in yesterday’s staff meeting — we can identify with Casper’s despair. We want to comfort him the same way we would want to be comforted, and the fact that the train doesn’t kill him is ironically funny because we know that poor Casper has no choice but to carry on.

This is the power of empathy — the unique human ability to care about and understand, with both our head and heart, what someone else is going through.

Perhaps we’ve been through something similar that reminds us how they must be feeling. We bear the scars of our own experiences — positive and negative. It’s only human to feel joy or pity when someone else confronts familiar circumstances. But empathy is as rational as it is emotional and arises out of our direct experiences.

Empathy is different from sympathy. Sympathy allows you to feel compassion and relate to someone else without ever having been in their circumstances.2 It is an emotional response, not a cognitive one. You obviously can’t know what it feels like to be a ghost unable to do away with himself, but it reminds you of situations where you were forced to soldier on yourself.

Most of us in western civilization recognize empathy in The Golden Rule — using our thoughts and feelings to do unto others as we would have them do unto us. But these principles are universal and never strictly selfless. Doing unto others as we would have done to us is as utilitarian for our long-term interests as it is for theirs.

Just as empathy inspires you to want something better for Casper, it can inspire you to intentionally choose to act in the best interests of your stakeholders ahead of yourself. Putting others ahead of ourselves is our definition of humility. Ironically, guile also requires empathy to seduce friends and foes to act on our behalf. The proper beguiling of another to help them get through difficulties is likewise borne out of deeply empathetic intentions.

The opposite of empathy is apathy, not antipathy or hostility. Apathy gives you permission to do, think, and feel nothing at all about the plight of another human being. Apathy is the chief emotional response of a narcissist and the quickest way to recognize one. Narcissists are absorbed with how everyone else perceives them. They are obsessed with constant external validation, and they find caring about others irrational, without an ulterior motive. When a person is so concerned with how others perceive them, it’s all but impossible for that individual to understand how others really feel about themselves. Apathy makes narcissistic indifference a kind of warped virtue.

Your Missionary and Mercenary have very different emotional responses to the plight of others. Missionaries default to sympathy, while Mercenaries tend toward apathy. A Missionary doesn’t need to have undergone similar struggles to feel compassion for another and want to help. But a Mercenary generally feels little urgency to assist unless they’ve come through something similar. The intellectual recognition of another's circumstances is where empathy — compassion to help plus the urgency to act — unites your Missionary and Mercenary to do things neither one can do alone.

Compassion without action is useless, but not all actions are created equal.

Successful simulation should be indistinguishable to the human mind from actual experience. Lessons learned in a simulated environment are just as valuable as the real-world scars we talked about earlier. But how can you systematically simulate scenarios of real risk and reward without putting your plans in peril?

The greatest risk of all might be failing to simulate how your plans could unfold in unpredictable ways, especially when revealed to the other stakeholders in the landscape. In the interests of those you serve, you must predict the right way to pursue the right actions at the right time.

The most important part of the competitive intelligence mission is fulfilled by understanding the motives and forces driving an organization or company and its leaders to choose a particular action or option at a particular time and place. Sometimes, this is entirely based on the instincts of a powerful executive. Other times, a history of past mistakes predestines your choices. A failed strategy wasn’t necessarily a bad idea; it might simply have been poorly executed and now irrationally drives you away from that option. Discovering why an action has happened in the past can help you understand why a similar set of circumstances might produce the propensity for a similar action in the future.

Empathy with competitors, customers, and other industry stakeholders helps you anticipate the response they will have to your plans when unveiled. The more you collect diverse perspectives from those other actors about their past experiences, motivations, and incentives, the better you can anticipate their range of possible reactions to adjust your execution.

Lacking this rationalization of empathy with other stakeholders, your Missionary and Mercenary will continue to conflict emotionally between sympathy and apathy. Only by balancing natural emotions with rational logic can you put your strategy to the test.

Thinking back to Chapter 2: Stochasm, the chisel tip’s geometry exemplifies this idea of appreciating diverse perspectives that paint a higher-resolution picture of reality. Illuminated from right angles, the chisel tip can cast three different shadows that are — all at once — a rectangle, triangle, and circle.

In other words, these contradictory shadows are simultaneously true characteristics of a singular object; truth is the three-dimensional geometry of the object itself. Truth alone has this unique and paradoxical ability to be described using contradictory traits and qualities we might find unbelievable.

From the Greek word, parádoxos, a paradox literally defines anything “beyond belief” using human logic. It’s what makes the search for truth such a gnarly pursuit in the first place!

Observing from each of these three orientations equips you to see topics, issues, and priorities from multiple perspectives as true, even when they contradict one another. Reconciling contradictions is how humans discover the truth buried under paradoxical and opposing characteristics of the singular truth. All human innovation comes from confronting contradictions in this way. A paradox is like an X on a treasure map — there’s gold buried beneath, and you should start digging!

But how can contradictory facts be true? Isn’t that the definition of a contradiction, that the facts cancel each other out?

As you first saw with our chisel tip example, facts about reality are mere descriptions of the truth, not the truth itself. Humans have a way of noticing only those aspects of our individual reality that must be immediately acted upon by us or our group.

All actions we consider are based on our dominion over two aspects of control:

the degree to which we have power that is ours alone — or authority as granted to us by others — over assets and activities integral to our success; or,

when we are dealing with an uncontrollable, governed by no one, but which we all must cope with to survive.

Dominion and contingency control factors reflect our power and the consequences behind how we act. In a macro-environment consisting of both helpful and hostile stakeholders, we must not simply consider our own actions, but also the actions and reactions of those other stakeholders.

In our fifty-odd years of collective intelligence experience, we’ve yet to discover a better way to simulate these actions and reactions than the process of imagining the future known as business wargaming. Also known by the more benign name competitive simulations, wargaming explores scenarios to understand the mindset of our friends and foes. But the real yield of a wargame comes from understanding and anticipating the control factors of the other stakeholders in our landscape. Understanding their control factors helps us plan out our next several moves, rather than assuming our original plans will inevitably succeed without assistance — or in spite of opposition — from other actors.

Other stakeholders have dominion and contingency factors, just like we do, which they have a degree of power over. Imagining their plans for surviving an uncontrollable event is a creative way for us to expand our own potential list of options.

We don’t have much influence over who wins the White House. But it is something we’ll need to cope with to survive. This is particularly true if our plans were made in a political or regulatory regime that’s about to change.

We don’t have any influence over whether the Federal Reserve Board of Governors will lower the overnight lending rate at their next meeting. But if our consumers suddenly have an easier time finding the cash to buy our products, we must consider how a rate cut might impact future demand.

“Not thinking it's possible is a failure of imagination.”

— Vinod Khosla

The plans of other stakeholders might affect plans of our own. If their plans seek to succeed at our expense, we should test our strategy by imagining how it’ll impact our future. We might not be able to influence them to do something else, but we can develop adaptable strategies for limiting the potential damage. If you’re an optimist, we might even imagine how to turn their success into a win for us, as well. As a strategist, you’ll never have more fun than when a disruptor reveals an unthinkable new pathway to profit for you.

But how can you simulate the actions of other stakeholders realistically enough to convince management to do anything differently? They have their best laid plans already in place, and you’ve been tasked to support the success of those plans, no matter what!

That’s why we intentionally position Simulation as the closing sequence of the Insights-to-Action Supercycle. Whether they’re doing it on purpose or by accident, your stakeholders’ plans are made in response to contingency and dominion factors. But people make choices without first understanding the contingency and dominion factors of other stakeholders. This is a problem identified long ago that leads to the inevitable failure of so many plans. We call that array influence control factors because we have some measurable degree of influence over how other stakeholders’ plans will be carried out.

Sometimes, the degree of influence is great. For example, if a person or group owns a subsidiary company with plans that might disrupt their own, management might intervene to adjust those plans to complement, rather than compete with, the larger strategy. Management of the subsidiary company will almost certainly adjust immediately or feel the wrath of the parent company!

Likewise, partners are interested in seeing you succeed so they can tag along. You might have lots of influence over their distribution of product in a channel, resiliency of a supply chain relationship, branding and advertising support work, or how a customer manages their security protocols. You might not have as much influence as you do with another actor you control or have an ownership investment in. But as partners, everybody should want to collaborate to succeed together.

Competitors are another story. A rival company with coveted market share should worry about how to protect their customers from you, just as you should worry about protecting your customers from them. Noncompeting stakeholders are not necessarily friendly either. Noncompetitors might enjoy a P1 status quo with Alphas and Betas that you’re eager to disrupt. But you’ll probably need to do that by redefining performance in Gamma or Delta. If their status quo is at risk, you might see some strange bedfellows materialize, something we’ll dig into further in this chapter’s Applied Case Examples.

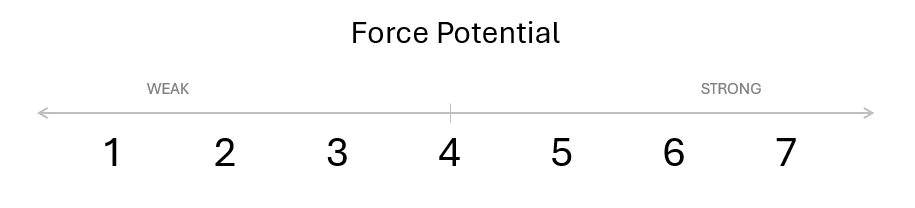

We like to think of influence control factors in terms of force potential. That means we recognize we have a much greater degree of influence over a friendly stakeholder and much less with a hostile or indifferent peer.

We suggest using a weighted system, such as 1 to 7, to estimate the relative influence we have over other stakeholders’ plans. You can make the numerical values anything you want, but we like to use odd numbers because it forces us to measure over or under a mid-point, known mathematically as the median. A force potential of 7 with a friendly subsidiary company that has a strategic rationale for complementing our plans might compare with a 1 for a direct competitor that will lose if we succeed.

Figure 14: Force potential measures your power to define the array of choice options other stakeholders consider, ensuring they will only consider options favorable to you.

On our 1-7 scale above, the median value is 4. If you have “very weak influence” over the actions of the other stakeholder, the value would be 1. For slightly greater than “very weak influence,” you might assign a 2 or 3. You would value “very strong influence” at 7. However, slightly less than “very strong influence” should earn a 5 or 6. A median value with 4 as the midpoint is simply the average influence you might exert to provide a rough order of magnitude across the range of other actors.

A simpler scale, such as 1-3, would place the midpoint at 2, with “weak influence” at 1 and “strong influence” at 3. This might be helpful if you don’t know much about the other actors in your landscape.

But if you know anything at all about how actors in the landscape compare to each other, you can be finer-grained in your assessment of force potential values with our 1-7 scale. The most important aspect of your scale is to have a clearly-defined median value that is a whole integer. This will make scoring your influence control factors much easier after your competitive simulation exercises have been completed.

Why don’t you measure your power to influence the actions of other stakeholders, rather than the force potential to alter the choice options themselves?

The simple answer is, because traditional definitions of influence measure your ability to change how they act or react after their choice is made. Force potential measures your power to define the array of choice options they’ve presented to themselves in the first place. This is a very nuanced view of influence. Is it better to push or pull an actor marginally in one direction or another after they’ve committed to a strategy? Or, is it best to guilefully define their options for them from the start and make it easy to commit to one you are sure to find preferable?

For anyone new to wargame simulations, this sounds a bit like hypnotism. It’s more scientific than that; it’s guile.

To the experienced wargamer, influencing other stakeholder choice options is the name of the game. Simply executing the strategy and adjusting on the fly will not imagine how other stakeholders are likely to respond realistically to your plans. You must understand the mindset and incentives other stakeholders will respond to in order to present predictable options for their selection. Although this is much easier to do with a friendly partner, it’s also possible with a competitor or other hostile, as well.

For example, let’s say you’re a new entrant in an adjacent market intent upon taking share from P1 incumbents in Alpha with your Beta offer that provides most of the performance value, costing 90 percent less. You know your processes will allow you to specialize around the least imitable sequence of the value chain to drive out most of the costs of production. But how will Alphas react to your offer being so cheap in comparison to theirs?

This cost structure advantage will challenge the incumbent Alphas to prove their non-specialized integration of the value chain is valued by customer segments with higher expectations of performance. This perception of value is already reflected in customer segment willingness to pay a higher price. But, buyer segments unconvinced by the Alphas’ value chain integration argument will predictably defect to your Beta offer. Since they are down-market with greater sensitivity to price and lower expectations of performance, they will be unwilling to continue paying 10 times your asking price for a simpler offer.

But won’t the Alphas react with a Beta offer of their own? Not without your understanding of the cost structure efficiencies only you — for the moment — possess.

This is the strategic hypothesis of your new market entry: If you can ally with one of the Alphas by offering a joint venture (JV) to create a subsidiary entity you co-own, you might provide that ally with a pathway to future competitive advantage in comparison with the other Alphas. Assuming you do this while lending them a measure of control over your joint venture, they will assume an implicit right-of-first-refusal to acquire the JV in its entirety someday.

The opportunity to disrupt the cost structure of other incumbents through specialization using your proprietary processes will be hard for the Alpha you’ve chosen to partner with to resist. All that remains is to make their right-of-first-refusal explicit in the terms and conditions of your JV agreement. The next section on Applied Case Examples will discuss in depth the possible evolution of this scenario. We’ll design a hypothetical wargaming exercise to focus on a channel conflict for a branded Alpha suddenly competing against a new entrant Beta with a private-label business model.

But how can you simulate a competitive response like that? Surely no incumbent competitor is about to willingly let you take share from them!

Here’s where the fundamental human instinct known as the enemy of my enemy is my friend kicks in. How a nascent partner will respond really depends on the salesmanship of your offer, as you communicate the inevitability of using your Beta to disrupt adjacent Alpha incumbents. If you can convince your partner you’ll be taking share from the other Alphas, you might find them shockingly likely to let you have it. That partner might also be willing to surrender down-market customer segments they find unattractive because of slimmer margins. This is particularly true if you can create a strategy for them via your offer of a JV designed to serve lower-end buyers.

How should we go about designing a wargame exercise that accounts for all of these abstract interests without it becoming paralyzingly complicated?

That’s where empathy plays its most important role. As Sun Tzu reminds us, if we know our enemy and we know ourselves, we needn’t fear the outcome of a hundred battles. But if we know our enemy better than they know themselves, we can make victory look downright easy.

The place to start with wargame design is to select the central strategy question you’re exploring with your teammates so a solution might be discovered. Wargaming is first and foremost a problem-solving exercise. But until you’ve focused your problem-solving capacity on defining the problem accurately — rather than becoming distracted by side-effects or symptoms of the problem — addressing the root cause of the problem will remain elusive.

While this is true for problems you control, problem-definition is especially important when exerting influence over other stakeholders who might be hostile to your power over them. Other stakeholders are quite likely to define the problem differently. Your ability to translate your offering — the apparatus that delivers your offers to market — to them as a solution will be based on how much better it addresses their problem than ideas of their own. As an operating model, the many different offers addressing each market segment could redefine performance for those unattractive buyers the Alpha has abandoned. But this will only happen if the offering you’ve developed to solve their problem is their path-of-least-resistance to the future.

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.” — Albert Einstein

Here’s a common business problem we’ve addressed with wargaming many times over the years: channel conflict. You notice channel partners starting to replace your sales volume with unbranded, knockoff suppliers willing to private-label products for them. There are various benefits to this for the channel, of course, assuming the product differentia are relatively unimportant to buyers and are mostly brand-related. Because brand is the last driver for overshooting Alphas, their dependency on brand recognition by buyers as a superiority criterion can be hard for them to come to grips with. This is especially true when confronting some bootleg offer introduced out of the blue.

Brand preferences are eroded by channel conflicts, especially when channel partners are seduced by private-labeling. This can have disastrous results for Alphas. We’ll come back to this in the next section to learn how to design a wargame exercise to solve this common Alpha strategy problem.

But can’t you just give me the short answer to learn how an Alpha should deal with channel conflicts?

To do that, we need to remember our Investment Grade Conjecture (IGC).

Acquisition is the default strategy for Alphas to deal with disruptors who succeed at eroding share. How to go about an acquisition becomes the Alpha’s IGC in the wargame. Valuation of the initial bid, structuring the terms and conditions of the acquisition offer, establishing thresholds for counter-offers, and deflecting competing bids are all elements of the IGC you should consider simulating.

Once an Alpha has decided to acquire the disruptor, the Alpha must align its own control factors with the other stakeholders it hopes to influence. Evaluating the intent behind the disruptor entity’s offer is the place to focus your questions. Was this invented specifically to be acquired by an Alpha like you and, if so, were you already top of mind for the new-entrant startup? Who else is being courted by the new entrant with a similar cost/benefit argument? What’s the net present value (NPV) of the deal in five years? Ten?

How you test an acquisition IGC is up to you, but you should assume the counter-parties are similarly able to test their assumptions against your own. As we’ve seen wargaming catch the imagination of C-suites everywhere in the past 30 years, assuming they haven’t simulated your reactions in response to their own can be very dangerous indeed.

Every wargame is designed to perform one specific task better than any other method: illustrate the emotional nature of decision making driving your actions. Producing the confidence required to act is a by-product of your tested strategy now that you’ve revealed the soft spots in your IGC. This revelation of weaknesses only happens through the friction imagined between stakeholders. The yield of the exercise is confidence in your strategy, but the method putting your strategy to the test — empathy — is what this chapter has been all about.

Empathy must imagine the reaction of friends to your plans, but you must understand how foes might react, as well. Skeptical teammates — often from legal, finance, security, or risk management — might drag their feet if you don’t imagine hostile reactions. The IGC might already be popular with your management team, but until you’ve simulated how it’ll be received by friends and foes, that skepticism might be the only thing standing in the way of a strategic disaster. Nobody wants to be the next Time Warner getting acquired by AOL!

Once you’ve created that sense of confidence among executives, it becomes a matter of consensus (and consent) before you can fund the IGC and swing into action with all the enthusiasm of your teammates and stakeholders behind you. You’ll hear more about consensus versus consent in Chapter 9: Actionable.

But first, let’s examine some Applied Case Examples where empathy was proven to be an important element of success. Simulating how other stakeholders might react to the central strategy question of your IGC helps skeptical teammates consent to your plans. It might even result in an enthusiastic consensus to move forward.

Applied Case Examples

The plot of the 1988 movie Rain Man unfolds around the transformation from pure Mercenary to a more balanced, empathetic mindset for one of the two main characters. Winning four Oscars at the 61st Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Dustin Hoffman, the film shows how the interplay between two strangers, joined by blood, leads to a lifelong family reunion.

In the film, collectibles dealer Charlie Babbitt (Tom Cruise) discovers he has a brother, Raymond Babbitt (Dustin Hoffman), whom he knows nothing about. Raymond, who lives in an institution, is an autistic savant with surprising and incredible cognitive skills. Because their father left most of his multi-million-dollar estate to Raymond, Charlie checks him out of the facility in a selfish attempt to take control of their father’s money. Along the way, however, Charlie discovers everything that Raymond is capable of. He comes to love Raymond and gives up his pursuit of the money in favor of a real relationship with him.3

During his preparations to work on Rain Man, Dustin Hoffman began to doubt his ability to play Raymond authentically and realistically. He even suggested that the producers try casting Richard Dreyfus to play the role instead.

In the end, thanks to his commitment to get the character right, Hoffman embraced method acting. This technique concentrates on realism and often requires the actor to go to more extreme lengths to embody a role. For Hoffman, this meant studying scientific papers on autism, talking to mental health professionals, visiting psychiatric facilities, and spending time with savants and their families. Because of this effort, Hoffman’s performance was widely acclaimed for its unique and loving portrayal of autism.

Had Hoffman not intentionally sought to empathize with people on the more intense side of the autism spectrum, he would not have been able to portray Raymond as authentically as he did. The millions of people who saw the film might not have had their assumptions challenged and grown to understand and appreciate what autism is or might look like.4,5

What does Dustin Hoffman’s commitment to empathize so deeply with autistic savants have to do with risk management’s impact on growth strategy for an organization?

Empathy-driven accountability ties directly to the ability to manage the risk to an organization and, as a result, support a growth strategy. Testing a strategy against the appetite and tolerance for risk requires a skeptical perspective that is less concerned about damaging morale. Just as Hoffman questioned his ability to portray Raymond, there must be a skeptical perspective challenging and testing the risks accompanying the growth strategy. Hoffman’s exhaustive method acting preparations gave him the necessary empathy to take the risk of portraying such an unusual character.

Growth-oriented executives tend to have a much higher risk appetite than their organization’s stakeholders are comfortable tolerating.

Risk appetite refers to the opportunistic seeking-out of carefully calculated risk to gain exposure to the rewards that risk makes possible.

Risk tolerance refers to how much risk a stakeholder can endure before quitting the endeavor and running away.

Organizations must reconcile their risk management apparatus with their growth strategy by controlling this ratio of risk appetite and risk tolerance. Equilibrium is reached when there is a high degree of confidence that the risks have been accounted for while growth opportunities are also achievable.

Mercenaries tend to be risk-seekers in pursuit of a profit opportunity. They always plan an escape route from most of the consequences of being wrong in their calculation of risk and reward. Missionaries, by contrast, tend to be risk-managers, preventing the losses that can come from risk-seeking activities that are too great for the enterprise to survive.

The relationship between opportunist risk seekers and survivalist risk managers is the key balancing act organizations of all kinds — but especially businesses — must master to endure.

Many companies default to letting their chief executive govern risk. Those with a balanced mindset between Missionary and Mercenary might even succeed. But relying on the CEO to govern risk is a lot like letting the fox guard the hen house. A leader’s job is to make things happen, not stop them from happening.

Unless you’re an investment management or holding company, risk oversight and governance should never be the primary role of the CEO. Growth should be. It’s really the board of directors who is tasked with ensuring the capital base of the firm is as safe as possible from the growth adventures of the C-Suite.

Making executives into stockholders was intended to extend this more modest risk appetite to management. However, the rise of insider trading, alongside automated trading algorithms watching for patterns to follow, seemed to defuse this mechanism. Ironically, as stock ownership by executives became a key component of their compensation to ensure a longer-range view of enterprise sustainability, the rationale for dividing the roles of CEO and Chairman of the Board fell into disfavor. This enabled CEOs to bully the board into rubber-stamping the strategy, rather than serving as a control mechanism on it.

Every CEO is a human being with a growth mindset. They’re seldom trying to talk themselves out of anything. The top of the executive food chain tends to attract personalities who thrive on building confidence in those they lead. Some are more in need of reinforcement than others, with both their plans and their personalities. What leader wants bad morale or a lack of confidence in their leadership?

For the CEO in whom stakeholder confidence has become a cult of personality, healthy skepticism isn’t as sought after as it could be. Take the example of Elizabeth Holmes and her 2018 charge by the SEC of defrauding investors with her blood-testing company, Theranos. The company’s board of directors failed to represent shareholder interests when they fell under the spell of the charismatic Holmes. Boards must be hypervigilant that a growth strategy isn’t just smoke and mirrors.

Leaders tend to seek out evidence that they were right in the first place about the strategy they’ve been entrusted by shareholders (under board oversight) with executing. In a culture where skepticism lacks value, management can be seduced by their own plans. The more successful they’ve been in the past, the more likely they’ll be to assume that track record represents infallibility.

But they’d be wrong.

Lacking sufficient humility to change their own minds when inevitable mistakes occur, leaders might also be unwilling to admit that they’re not as objective as they should be. If they’ve recently been brought in from the outside, they might also lack an understanding of shareholder will, which can lead to mistakes about the amount of risk accompanying their growth hypothesis (see Chapter 2: Stochasm).

Because their natural bias skews optimistically toward whatever might bring larger returns, there is a tendency for a CEO to be too optimistic as they calculate their forecast expectations. Objective risk management must happen elsewhere as a result. The opportunistic CEO must be balanced by a survivalist’s mindset.

The CEO is held accountable by a chief risk officer overseeing a risk management function calibrated to the contingency, dominion, and influence control factors confronting the enterprise.

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank — also known as SVB — in March 2023 demonstrates this conundrum. Leaders at the bank served primarily startups and venture-backed firms, with most of their depositors’ market share derived from industries like healthcare and technology. SVB used most of those deposits to buy safe Treasury bonds and other long-term debts with lower risk than other debt instruments, such as commercial real estate loans.

When interest rates started rising in 2022 due to the Federal Reserve’s attempt to control inflation, investors could buy bonds yielding much higher interest rates. This caused Silicon Valley Bank’s bond portfolio to decline in value. This contingency control factor was compounded by customers’ withdrawal of funds as they realized returns were much higher elsewhere.

Silicon Valley Bank was forced to sell some of its investments at a loss to generate the cash needed for depositors to redeem their funds. Compounding the risk by an order of greater magnitude, rollback of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2018 meant that, as all of this was happening, the bank didn’t have enough reserve assets to meet demand for deposit flight to higher-yielding assets. As deposit flight accelerated in early March 2023, the risk of contagion led the Federal Reserve to establish the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) to backstop the sale of devalued assets by any bank needing to raise capital to redeem deposits. This effectively socialized and monetized the banking system.

Taking reserve requirements from 10 percent to zero would unlock access to tens of billions of dollars in capital for banks to put to work in the innovation and entrepreneurial economy. But the fact Silicon Valley VCs could move billions of dollars between accounts with apps on their mobile phone was a mixed blessing. Who could have predicted putting all of that capital to work would backfire when depositors demanded their money and didn’t even need to run to the bank to do so?

What could go wrong? The problem with SVB was that no one asked that question.

As contagion started to spread, the BTFP move by the Fed did nothing short of preventing the collapse of the banking system. Deposits over the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit had been guaranteed by the Treasury. And, with it, the monetary masters of the universe guaranteed the entire debt-based financial milieu, which had been in place since Nixon ended the gold standard on August 15, 1971.

At least, for the moment.

Ultimately, the Federal Reserve would point the finger for SVB’s liquidity breakdown at both the senior management team and the board of directors. Senior executives had mismanaged the investment risk of their balance sheet until it was too late, and the board failed to provide checks and balances against risk-seeking senior managers.6

But SVB wasn’t alone in their mismanagement. The systemic lack of reserve requirements had made these conditions possible. And the banks themselves were still responsible for their future viability in the face of changing customer circumstances.

The world in which their growth strategy was born had suddenly changed. Unfortunately, nobody noticed. More accurately, it was nobody’s job to notice.

The general counsel for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Richard Ostrander, noted in a July 2023 speech that growing a business is the responsibility of the CEO. But the risk management function at SVB was temporarily overseen by the CEO’s office, as the chief risk officer role was vacant. Ostrander went as far as saying that the failure would not have occurred if a chief risk officer had been in place.7 Had there been a risk executive, separate from the C-Suite, occupying the role of noticing when macro-environmental consequences to their growth strategy changed, the lender-of-last-resort would not have been needed at all.8

Perhaps by monitoring some indicator of those changing conditions, risk management might have forecast for the board how to reel in the growth strategy to account for those changing conditions. In aggregate, there’s no better indicator than when subject matter experts change their sentiment. In this case, the sale of SVB stock by insiders, such as the CEO, would have been enough of a red flag to open an inquiry into what they knew and when they knew it.9

What does the story of SVB above have to do with Frank Capra’s 1946 film, It’s a Wonderful Life?

In Capra’s movie, the well-intentioned Missionary protagonist, George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart), operates the town’s humble Building & Loan. Focused primarily on the mission of the business — making loans for people to own their own home — instead of pure profit, George fails to anticipate how depositors will respond to a bank run. They all rush to withdraw their money. Because he hadn’t been looking for signs of the financial crisis or ensuring the Building & Loan had the capital to address the risk, George is forced to scramble and use all the personal money he has to keep the depositors from closing their accounts. His offer provides only a temporary liquidity fix and doesn’t address the long-term worry the depositors have.

Sometimes, a Mercenary perspective can empathize far better than a Missionary can. Bailey’s rival, Henry Potter (Lionel Barrymore) — a pure Mercenary — was able to empathize with depositors who feared their money might evaporate on them: “I may lose a fortune, but I’m willing to guarantee your people, too. Just tell them to bring their shares over here and I will pay 50 cents on the dollar.” As he beguiled the depositors by withholding the truth — that his offer was intended to bankrupt George as a competitor — Potter’s apt understanding of how the people felt became a weapon that put him in a better position to win.10

Much like George, SVB’s CEO didn’t fully appreciate the hesitation depositors were feeling about returns on their cash. It’d be a stretch to call SVB’s CEO empathetic to customers, since there’s no doubt the growth strategy missed the potential consequences changing interest rate dynamics would have on their priorities. SVB’s deposit flight had not yet reached the fever pitch it did for the humble Building & Loan. But a dedicated risk officer would’ve had no other job than to observe, notice, and advise how to act.

What about our channel conflict case of an Alpha offered the chance to adjust to the changing economics of a Beta before its competitors can? In the example below, we’ll show how indirectly-competing peers in Alpha can spread the risk of adventuring into a Beta JV together and test how to elevate relevance to a larger buyer segment.

One example of a new entrant Beta enticing incumbent Alphas down-market is the move by universities over the past decade to offer their sunk-cost lecture content free online through Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Their lectures are made available free of charge to anyone around the world interested in the subject matter. Coursera attracted Ivy League institutions like Stanford, Duke, Princeton, and Johns Hopkins, while non-profit peer edX recruited MIT, Harvard, and UC-Berkeley.

What’s the motivation for the university and their faculty to shift down-market with a Beta JV?

For Stanford computer science professor and Coursera co-founder Andrew Ng, it’s all about numbers and reach. Ng once taught an online class to more than 100,000 students, but remarked that, to reach that many in his regular lectures, "I would have had to teach my normal Stanford class for 250 years."11

But if these courses are all given away for free online, how could Coursera or edX offer these Alpha universities a path to future revenue?

That path is uncertain. The benefits are probably more related to the reputational value their brand might enjoy as a result of offering their learning to an audience less willing or able to pay than the Alpha might be able to reach without them.

The real benefit to the Alphas in online learning like this isn’t income, but relevance. The next generation of learners and the business models that will serve them are abstract and sophisticated enough that no incumbent has the risk appetite to go it alone. Fortunately, universities are more willing to explore new and innovative territory together because of their relatively low risk tolerance.

Without paying the $50,000+ required to attend these world-class universities, millions around the world learning for free could transform the mission and model of higher education. President of edX, Anant Agarwal, calls it "the single biggest change in education since the printing press."12 Any university board of regents representing a diverse cadre of stakeholders has a duty to balance growth and risk. It boils down to making sure the risk of joining such a Beta experiment is less than the risk of not joining it.

The MOOC Beta has not been a successful experiment, at least by the measure of the universities. A 2018 MIT study found only about 3 percent of MOOC participants completed their course of study.13 But earning a completion credential was never the offer. Exposure to an exponentially greater number of learners was the principal benefit to world-class universities repurposing lecture content together in this way.

Now that you’ve seen how a Beta JV can help Alphas correct their Angle of Attack down-market, we’ll return to our channel conflict wargame design example where a single Alpha is lured into Beta in Chapter 9: Actionable.

Which mindset is strongest in you?

“You want the moon? Just say the word, and I’ll throw a lasso around it and pull it down.” — George Bailey

[From the film, It’s a Wonderful Life, based on a short story called The Greatest Gift by Philip Van Doren Stern, 1943]14

As a moral idealist, a Missionary serves a just cause that will seldom be achieved in their lifetime. For them, progress toward achieving that just cause is the goal, not a win ending in personal or team success.

A Mercenary, by contrast, is the amoral pragmatist with a winning aspiration and the need to achieve more immediate objectives. They define success as the ending of an engagement having achieved a here-and-now result.

Missionaries use empathy to help others get what they want while making progress toward the ideal, while Mercenaries use empathy to maneuver friends and foes alike to respond in predictable ways that enable their pragmatic win. Our Missionary and Mercenary have never been more similar than in their use of empathy to influence others by motivation and incentives to collaborate. The differences are subtle, even indistinguishable at times, but their goals are not.

Suppose someone has a resource or talent you lack for a project you’re working on. Your Mercenary will exploit their desire to express their gift or ability in exchange for benefits they would enjoy in return — praise or a paycheck, for example. On the other hand, the Missionary would help them feel like they’re part of something bigger than themselves and that we are working towards the greater good. They would help the individual to enjoy the altruistic act of giving and the positive emotional benefits that accompany being generous with one’s talents.

The concept of loving your enemies through Missionary and Mercenary motivations has been revealed time and time again in our careers in competitive intelligence. Most leaders are annoyed and irritated by their competitors. Many who’ve suffered from a rival’s actions might even call what they feel towards them hate. You, too, might prefer your competitor to suffer or die a deserving death. You might even wish they’d never existed in the first place.

But your competitors are there for a reason. Competitors motivate you to be more accountable to yourself and your stakeholders, and they influence the standards you operate under. They can pull ahead if you fail to address your inherent weaknesses, unforced errors, strategic mistakes, or looming threats.

Should you choose to see them this way, competitors make you better, more efficient, honest with those who trust you, and innovative in meeting unmet needs. They push you to better serve customers who consume your products and services. They also reveal opportunities that can help you score immediate wins, and they can help you establish your long-term market position. You should be grateful for everything you learn from your competitors because those lessons will make it easier to make intentional choices about what to do next, even if that choice is to take no action at all.

We’ve worked hard to help companies confront the kinds of crossroads moments we all face eventually. All along, our appreciation has grown for the idea that information isn’t intelligence unless it can produce action. Even the best insights, without action, are just facts. We’ve also kept the full definition of stakeholder in mind: anyone who stands to win or lose as a result of the actions taken from your analysis or findings.

Armed with these principles, we acknowledge that even helpful stakeholders can still respond in unpredictable ways. When probable responses are miscalculated, entropy kicks in and action grinds to a halt. Empathy minimizes these miscalculations and keeps responses predictable enough to continue moving forward.

Although most of your known stakeholders will presumably help you, not all of them will want you to succeed. Sometimes, a presumed ally will betray you. Others will be intentionally incompetent to slow your progress. This term encompasses everything from dragging feet to assigning responsible people to inept tasks. Intentional incompetence is central to the CIA’s manual of “simple sabotage” written after World War II to slow the Cold War spread of Communism.

These behaviors, which make effective organizations ineffective, are everywhere, and they’re the same behaviors that show up when analytics go from predictive to palliative. We seek out data that makes us more comfortable over data that presents a harsher truth. Empathy helps you to identify and mitigate these passive-aggressive hostiles and stop letting them thwart your progress.

Empathizing with malevolent actors can reveal the fear or injury that makes them such a negative force. If you can understand the reasons why they behave so badly, sometimes, a relationship can be built to address them, and enemies can be converted to allies.

Hypocrisy gets in the way of leaders using empathy to energize their stakeholders. A leader who cannot hold themselves accountable will have a difficult time convincing one of their teammates that rules or expectations should apply to them. Leaders model accountability for their people; but without empathy, leaders will never understand why others might perceive their hypocrisy so poorly.

Culture is the sum of the behaviors leadership will tolerate. Therefore, leaders must hold themselves to a standard higher than their organization or risk their best and brightest finding a more authentic place to work.

Empathy enables you to be realistic and loving in terms of how high you set the accountability bar. Everyone has different gifts, and those gifts are seldom of equal value to the mission of an organization or team. You can adjust your expectations of others to meet them where they are when you know which abilities they bring to the table. You would not expect an analyst with three years of experience to perform at the same level as someone who has 30.

Controlling risk in a way that achieves superiority and growth objectives requires the C-suite and risk management function to work cooperatively together to balance risks and rewards. They cannot do this if they do not empathetically understand two elements: the desires and needs of customers, which are the basis for the CEO’s growth projections; and, the expectations of Wall Street or how other investors calculate different variables affecting their own risk appetites and tolerances. This balance can require some degree of experimentation before everyone has a clear picture of the reality confronting them, but it is essential for long-term success to be possible for all stakeholders.

There is always going to be friction between innovators and the financiers who must put up the capital to underwrite the losses a new innovation will initially sustain. But empathy between them allows us to see risk and reward from the perspective of other stakeholders and remember that we’re on the same team.

Whether you’re the innovator or the financier, the important part is to empathize with a perspective different from your own to gain a higher resolution picture of reality. This is precisely what the Missionary and Mercenary do for one another. And as you’re about to learn, it’s exactly what our parents taught us growing up.

Memoirs

Losing our parents was heartbreaking, but in different ways.

We didn't have the opportunity to say goodbye to Dad because he was taken so suddenly, quite literally dying of a broken heart when an aortic aneurysm ruptured. Our top concern was caring for our mother, who was now grieving after our father saved her life in his final act of bringing their car safely to a stop. Living with the thought of losing Dad was an inevitability we’d all been prepared to confront for more than 20 years. But it was still a shock when it happened.

We learned of Mom’s cancer some months before it moved to her liver, so together, we had a chance to come to terms with the inevitable. But that introduced new anxieties for us as we hoped to make her as comfortable as possible. When we moved our mother home from Knapp Haven for her final days, hospice was there to care for her while we waited at her side to say our last goodbye. We didn’t know how long she had, but we knew time was short. We would spend whatever hours remained watching over her, holding her hand, and letting her know she wasn’t alone. We’re happy we could honor her last request to pass peacefully in the house she knew as home from the time she was a little girl.

Hospice care is palliative. It’s designed to make you more comfortable while you’re dying. Over the years, we’ve noticed most intelligence analysis is often similarly palliative to leaders.

Instead of being as predictive as leaders expect it to be, intelligence analysis tends to reinforce more comfortable assessments of the future and downplay the serious risks surrounding the current strategy. Truly predictive analysis requires revelation of harsh realities, which is especially difficult for people who have a hard time handling bad news. Many leaders find such untempered truth-telling needlessly damaging to morale. The result is their failure to do anything to save themselves until it’s too late, despite a recognition that something's slowly killing them.

We’ve gained this professional perspective from watching companies struggle and occasionally die. Sometimes, the struggles were slow and painful. Other times, they were mercifully quick. But through these experiences, we’ve gained a deep sense of empathy for those who struggle. We intentionally study competitive examples where contenders became losers so that we can understand what went wrong and prevent other companies from making the same mistakes in the future.

A few years ago, Arik realized why he was so drawn to history. All of the periods, places, and people led him to the same question: When do viable contenders make the inextricable mistakes that end in death?

On top of that question, we ask a related one: What does it take to save a dying company?

Arik’s hay fever offers a clue.

When Arik was just four years old, the Johnson family got invited to a picnic at a nearby farm. Arik spent the day playing beneath a gigantic pine tree with the other children. But that evening, our mom was sure he was going to die from the most severe allergy attack anyone had ever seen.

Arik’s immune system overload from the tree pollen was so severe that he’s had fairly serious hay fever ever since. For some of his adolescent years, Arik received regular allergy shots. The goal of the shots was to expose him to the allergens he was reacting to, trigger his immune system’s antibody response, and over time, get his body familiar enough with the allergens so that his immune system could ignore them when commonly encountered in the environment.

If we reveal too much of the truth too soon, our stakeholders can have a kind of psychological immune system reaction. Not unlike what happened to Arik’s actual immune system after that fateful playdate on the farm, they’ll potentially suffer from similar reactions in the future. Simulation prevents this overreaction to reality.

Missionaries beguile stakeholders by gradually revealing true circumstances as they slowly grow more resilient in handling bigger doses of truth. By exposing them little by little, they can come to accept otherwise unthinkable realities that would have previously triggered an overreaction. Exposure therapy, just like an allergy shot, is a common strategy to alleviate physical or psychological suffering by making the stimulus more familiar to an involuntary system. This helps the sufferer respond less severely when encountering that stimulus in the wild.

Most of the clients we work with have no shortage of this Missionary mindset available. They tend to lack, however, the Mercenary mindset of emotional indifference to the trials and tribulations they might encounter. They’re just too close to the realities their company is confronting. Mercenaries require recognition of their own past experiences to make empathy a rational response. This is one of the reasons we play that role when wargaming clients can’t do it themselves.

We have come to understand how critical empathy can be in making the kinds of choices that deliver superiority. Reflecting this importance, we’ve incorporated empathy into the training and development we do with leaders and their organizations. Beginning years ago at one of our RECONVERGE summits, we started spending the final day applying empathy as a competitive advantage as we simulated the future of three sectors important to everyone — food, health, and money.

We designed a wargame simulation in which the participants, organized into teams, had to play the role of specific companies trying to out-compete each other for the approval of the market team. We then presented them with realistic events that would alter their plans to see how they’d react. The market team judged which of those reactions were favorable and which were mistakes, and scored them accordingly. It’s hard to forget a great idea being destroyed by a market team’s critique! Even if the lesson learned was contrived from an imaginary scenario, the memory of the lesson lasts a lifetime.

In our experience, empathy comes a bit more naturally to women. As a result, men have to work a little harder if they want to be as effective using empathy as a competitive advantage. This concept came out in a July 2022 Running Into the Fog podcast with our dear friend, Melanie Siewert.

Melanie is one of the most experienced and savvy intelligence and marketing executives we’ve been privileged to know. She asserted that, when you put yourself in someone else’s shoes to understand how they feel, your analysis is more likely to resonate with them. Without appreciating their circumstances, you won’t be able to consider their response to possible scenarios and make suggestions they’ll find actionable.

Melanie made the point that women are often more successful in competitive intelligence because of a greater cultural latitude to express interpersonal empathy in comparison to their male counterparts. This difference in expectation can turn into an advantage in any situation where a personal connection has the power to influence your outcome.

Spending time with college students is one of our favorite forms of outreach. Remembering when we ourselves confronted a world of infinite possibilities reminds us where we come from and reactivates the hopes and dreams of young adulthood.

Attracting the interest of the best, brightest, and most energetic minds of this generation provides a pipeline of passionate and talented new professionals to the field. It is our aspiration that the lessons contained in this book, particularly walking in the shoes of others with empathy, will provide the kind of direction that is so necessary when possibilities overwhelm us. We are privileged to have many teammates with degrees from places like Mercyhurst, Gannon, and Concordia University of Wisconsin. Offering our programs at each of these institutions has taught us as much as it’s taught the students.

As higher education recalibrates offers for the superiority criteria the market will reward with share, we look forward to confronting these challenges with all of our university partners. By remembering where we came from, we can imagine where the world will reward us for going next.

Questions to Activate Empathy

Despite the benefits empathy has to offer the analyst, few such job descriptions list empathy as a prerequisite, although we think they should. Empathy more often is seen as a soft skill with no technical contribution to the impact of the insights an analyst is creating. With little willingness to consider the circumstances of a stakeholder’s point of view and priorities, leaders tend to skip over the human progression from humility to guile, and eventually empathy, in pursuit of actions they believe will be valued by the business.

But how confident are leaders about the actions they’re about to take when the options and recommendations were produced without regard for how stakeholders feel about executing them? Could this be why so much intelligence analysis is regarded as never producing as much value as originally promised?

Requests for analytic insights don't guarantee that action will be forthcoming. Coming to the table, unwilling to act, ensures more palliative results will overpower predictive ones. Analysts and leaders must understand each other’s priorities and aspirations, constraints and fears, to help the organization realize a payoff from the insights it's paying for.

We seem to be surrounded by narcissistic forces unable to imagine what it’s like to walk in someone else’s shoes because they’re too concerned about what the world thinks of them. We see growing social divisions often based on the false dichotomy between right and left political extremes. How have you seen both sides dehumanize the other, making empathy much harder?

If you can understand why someone believes differently from you, you will be offered the rare opportunity to change your mind. Agreeing to disagree is not merely forgivable, it’s necessary for a civil society. And you might just learn you’re not as smart as you thought you were. Have you ever experienced a change of perspective on something you were absolutely certain about?

Empathy provides a pathway to reunification that permits us to see the extraordinary in the midst of the ordinary.

This is the type of reconciliation portrayed in the film, Rain Man. Have you ever encountered a person, differently gifted, perhaps even on the autism spectrum, whose astounding attention to detail or photographic memory could be channeled into something amazing?

Grasping the power empathy offers to bridge the gaps that threaten both civility and innovation, think back to Chapters 4-6 (Disruption, Superiority, Humility) from Section Two: Optimality. These chapters demonstrate the importance of intentionally sacrificing suboptimal options. The choice that remains is the only choice that wins. Simulation, in which empathy serves as the centerpiece between guile and actionable, highlights another immutably human characteristic — hope.

Hope, to paraphrase the Architect in The Matrix Reloaded, is that quintessential human delusion that is simultaneously the source of our greatest strength and greatest weakness.15,16 It answers the question, why would anyone bother to innovate at all? Why would you beguile someone to help them cope with reality? Why would you go out of your way to assist another’s action before it’s too late?

It’s all because you have hope for a better future. For your Missionary, that hope is divinely inspired and directed. For your Mercenary, it’s simply utilitarian for the greatest number of stakeholders.

We’ve all made choices we regret. Choice involves anticipating the grief of sacrifice as a prerequisite to making a selection. There’s always an opportunity cost whenever you commit to one option alone. You forsake less optimal options because you have hope that your choice will make a difference, in your life or in the lives of those entrusting you with their leadership. Having the experience of choosing poorly in the past, how can you use the potential for regret or grief to choose the best option going forward?

Technology has always helped make human strategists better. Yet, machines are incapable of making sacrifices in the way human beings can because machine intelligence will only ever imitate hope, which is based on the dreams of the human heart.

Strategy always depends upon real people — human intelligence — regardless of how advanced our AI or other high-tech tools might appear.

Empathy that helps you feel what others feel to predict the actions of your friends and foes is a capability you can intentionally leverage to produce more successful results for yourself and others. Without empathy, any assumptions you make about how other actors will respond to your plans will be little more than guessing. The resources and capital allocated to your IGC are needlessly put at risk by refusing (or simply forgetting) to consider how allies and enemies will try to help or hinder your plans.

When empathy has exposed those probable reactions, you’ll be free to act with confidence. Next, in Chapter 9: Actionable, you’ll learn how to mobilize your insights into confident action by your teammates and stakeholders.

References:

Inter-Pathé, “Casper Famous Studios The Friendly Ghost 1945,” Youtube, October 23, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muauhWrT9TQ.

Regan Olsson, “What’s the Difference Between Sympathy and Empathy?”, Banner Health, December 18, 2021, https://www.bannerhealth.com/healthcareblog/advise-me/difference-between-empathy-and-sympathy.

“Rain Man Plot,” IMDb, accessed March 20, 2023, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0095953/plotsummary/?ref_=tt_ov_pl.

Associated Press, “‘Rain Man’ — The Role Hoffman Almost Quit,” Deseret News, December 29, 1988, https://www.deseret.com/1988/12/29/18789719/rain-man-the-role-hoffman-almost-quit.

Darold Treffert, “Rain Man, the Movie,” SSMHealth, August 3, 2021, https://www.ssmhealth.com/blogs/ssm-health-matters/august-2021/rain-man,-the-movie.

Erin Gobler, “What Happened to Silicon Valley Bank?”, Investopedia, September 28, 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/what-happened-to-silicon-valley-bank-7368676.

Richard Ostrander, “Remarks on the Panel ‘Bank Crisis Framework: Learning from Experience,” June 17, 2023, https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2023/ost230617.

James Lee and David Wessel, “What did the Fed do after Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed?”, Brookings, January 25, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-did-the-fed-do-after-silicon-valley-bank-and-signature-bank-failed/.

Robert Frank, “SVB execs sold $84 million in stock over the past two years, stoking outrage over insider trading plans,” CNBC, March 14, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/14/svb-execs-sold-84-million-of-the-banks-stock-over-the-past-2-years.html.

“It’s a Wonderful Life Plot,” IMDb, accessed October 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0038650/plotsummary/.

Andrew Ng, “Andrew Ng: 2012 Plenary Session,” Stanford University, April 3, 2012, http://www-forum.stanford.edu/events/2012/2012andrewnginfo.php.

Rebecca Rosen, “‘The Single Biggest Change in Education Since the Printing Press,’” Yahoo!Finance, May 2, 2012, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/single-biggest-change-education-since-175834183.html.

Doug Lederman, “Why MOOCs Didn’t Work, in 3 Data Points,” Inside Higher Ed, January 15, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/01/16/study-offers-data-show-moocs-didnt-achieve-their-goals.

“The Greatest Gift, About the Book,” Simon and Schuster, accessed October 11, 2024, https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Greatest-Gift/Philip-Van-Doren-Stern/9781476778860.

1RiotKing, “The Matrix Reloaded — The Architect Scene 1080p Part 1,” Youtube, March 1, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHZ12naX1Xk.

1RiotKing, “The Matrix Reloaded — The Architect Scene 1080p Part 2,” Youtube, March 1, 2017, https://youtube.com/watch?v=LN8EE5JxSGO.